Latest Articles

Strategic Planning in University Athletic Departments in the United Kingdom

Abstract

The study’s purposes were to (a) determine the extent to which university athletic departments in the United Kingdom use strategic planning, (b) identify key factors discouraging strategic planning, and (c) examine relationships between use of strategic planning and the variables university size and athletic director’s background. Of athletic departments studied, 59.5% were strategic planners that wrote long-range plans, assessed external and internal environments, and based strategies on department mission and objectives. The remaining 40.5% were nonstrategic planners using just some components of the strategic planning process, as either users of short-range written plans and budgets, for the current fiscal period; users of unwritten short-range plans maintained in an administrator’s memory (intuitive planners); or users of no measurable planning procedures.

Keywords: planning, strategic planning, strategy, university athletic departments

Private and public organizations today use a structured planning process to select appropriate long-term objectives and develop means to achieve these objectives (Christensen, Berg, Salter, & Stevenson, 1985; Elkin, 2007; Mintzberg, Lampel, Quinn, & Ghoshal, 2003; Wheelen & Hunger, 2008). The business sector of society has long recognized that continued profitability requires maintaining a strategic fit between organizational goals and capabilities and changing societal and economic conditions. As its environment changed, the business sector developed planning systems which made possible coordinated and effective responses to increasing unpredictability, novelty, and complexity (Ansoff, 1984). Strategic thought and practice generated in the private sector can also help public and nonprofit organizations anticipate and respond effectively to their dramatically changing environments (Bank, 1992; Bryson, 1988; David, 1989; Duncan, 1990; Espy, 1988; Laycock, 1990; Medley, 1988; Nelson, 1990; Robinson, 1992; Wilson, 1990).

Today’s colleges and universities have experienced rapid change. Educational administrators are confronted with changes associated with aging facilities, changing technology, changing demographics, increasing competition, rising costs, funding cuts, and so on. The educational sector has begun to recognize that strategic planning is necessary in order to maintain responsiveness to the rapidly changing environment (Agwu, 1992; Busler, 1992; Hall, 1994; Williams, 1992). Since athletic programs are so much a part of colleges and universities, athletic departments face the same problems as do the institutions to which they belong. If athletic departments are to respond well to change, they must anticipate it and adapt programs and resources to meet their mission and objectives in new situations (Bucher, 1987; Kriemadis, Emery, & Puronaho, 2001). Strategic planning may help athletic departments do this and may further point them to the strategies necessary to achieve their missions and objectives (Dyson, Manning, Sutton, & Migliore, 1989; Ensor, 1988; Gerson, 1989; Kriemadis, 1997; Smith, 1985; Sutton & Migliore, 1988).

Duncan (1990) stated that strategic planning is a method of decision making developed in the private sector that has been adopted by public sector organizations. Proponents of strategic planning argue that traditional long-range planning fails in the contemporary world, and strategic planning is now the powerful tool for organizations to cope with an uncertain future.

The service sector today includes a growing nonprofit segment, including social services, schools and universities, research organizations, sports organizations, religious orders, parks, museums, and charities. Strategic planning is earning its place in the management systems of service businesses (Kriemadis, 1997; Kriemadis et al., 2001; Sutton & Migliore, 1988; Wilson, 1990). Pearce and Robinson (1985) have argued that strategic planning consists of the following steps:

1. Determining the culture, policies, values, vision, mission, and long-term objectives of the organization.

2. Performing external environmental assessment to identify key opportunities and threats.

3. Performing internal environmental assessment to identify key strengths and weaknesses.

4. Developing long-range strategies to achieve the organization’s mission and objectives.

5. Establishing short-range objectives and strategies to achieve the organization’s long-range objectives and strategies, a process called strategy implementation.

6. Periodically measuring and evaluating performance, a review known as strategy evaluation.

Steps 1–4 together are referred to as strategy formulation.

A number of authors (Ansoff & McDonell, 1990; Barry, 1986; Bryson, Freeman, & Roering, 1986; Bryson, Van de Ven, & Roering, 1987; Elkin, 2007; Kotler, 1988; Mintzberg et al., 2003; Rowe, Mason, Dickel, & Snyder, 1989; Steiner, 1979; Wheelen & Hunger, 2008) argue that, in turbulent environments, strategic planning can help organizations to

- think strategically and develop effective strategies

- clarify future direction

- establish priorities

- develop a coherent and defensible basis for decision making

- improve organizational performance

- deal effectively with rapidly changing circumstances

- anticipate future problems and opportunities

- build teamwork and expertise

- provide employees with clear objectives and directions for the future of the organization and increase employee motivation and satisfaction

Wheelen and Hunger (2008) and Newman and Wallender (1987) stated that basic management concepts should be applied to both profit and nonprofit organizations. The present study is useful in extending the basic management concept of strategic planning to university athletics. It may help athletic administrators to further their understanding of the strategic planning process in their respective athletic departments.

Management of University Athletic Departments in the U.K.

Both the nature and context of sports programs in the United Kingdom—and specifically of sports in higher education there—have changed in unprecedented ways in the last decade. For instance, public income per student has declined by 40% in real terms, and universities have responded by rapidly expanding student numbers and developing alternative income-generation activities involving nongovernmental sources (Lubacz, 1999).

Sports in the university sector in the U.K. has historically been managed by each university’s athletic union, a largely student-run body attached to the student union. The role of the athletic union, the fact that students belonging to it are untrained, and the voluntary nature of athletic union offices (filled annually by election) have rendered management of university sports largely ineffective, strategic planning virtually nonexistent. But sports’ profile has increased considerably, as has the value attached to sports. Many universities in the U.K. have already recognized that by managing their sports programs more effectively, fully endorsing a corporate-type strategy within their athletic departments, they should be able to develop new opportunities at local, regional, national, and even international levels. To establish a rationally planned and coordinated approach to sports, many universities have introduced relatively formal sports management structures. These have often involved full-time paid positions emerging from either academic departments, central services, or, more directly, from a university’s student union.

Because the scale and scope of such developments in university athletic departments over the last five years have varied widely, university sports in the U.K. now involves many diverse approaches to management. At one extreme, some universities still feature programs run entirely by students for students. At the opposite end of the continuum, some universities have recently created institutes of sports that are separate cost centers employing up to 20 staff members or more. Such institutes of sports aim to fully realize roles that may include (a) encouraging and supporting sports participation by students and staff, (b) establishing the university’s place as a center of excellence in sports, (c) managing the university’s sports facilities, programs, and events, and (d) organizing short courses, seminars, conferences, research, consultancy, and publications that reflect both university expertise and strong international, European, and regional links enjoyed by the university (Ilam, 1999).

Thus the functions of university sports and the nature of university sports programs are now considerable in some cases, much broader than campus athletic clubs and student competitions. Stakeholders can include internal and external clientele: participants, spectators, coaches, administrators, sponsors. Sports products and services can relate to anything from merchandising to organizing short courses; from national athlete awards to requirements of degree study in sports-related areas. University sports facilities can be used for a variety of leisure purposes over all 52 weeks of a year, and the meaning of recreational sports can extend to providing personalized health fitness programs. Consequently, within higher education, sports has a growing, diversifying audience, only one part of which is involved with competitive performance. Many universities have positioned themselves accordingly, establishing the balance and management practices to meet new needs.

Where universities and their students wish to compete against one another, either nationally or internationally, they must become institutional members of the British Universities Sports Association (BUSA). This voluntary association has its origins in the first intervarsity athletic meeting between nine institutions from England and Wales, held in 1919. Since that time, membership eligibility has been limited to U.K. institutions of higher education, but in 1999 BUSA had 148 members and some 200,000 students participating in nationally organized championships in 43 different sports (BUSA, 1999).

The present study addressed two research questions: (a) To what extent do university athletic departments in the United Kingdom use the basic management tool of strategic planning? and (b) What are the key factors discouraging athletic departments’ use of strategic planning? In addition, the study tested the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. The extent to which strategic planning is used by the athletic department of a U.K. university is independent of the university’s size.

Hypothesis 2. The extent to which strategic planning is used by the athletic department of a U.K. university is independent of the background of the university’s athletic director.

Method

Population

The population for the present study consisted of 101 of the 148 institutional members of the British Universities Sports Association (BUSA). The 101 BUSA members studied represented all U.K. universities that had participated in more than 10 sports competitions during 1999 and that furthermore employed a full-time coordinator of sports. These criteria were established in order to ensure participation by sports planning units large enough to pursue the kind of strategic planning under investigation. Surveys were sent to the athletic departments of the 101 BUSA members. Out of these, 37 responded (37% response rate). Nonrespondents’ characteristics did not appear to follow a pattern of geographical location or institutional size. This fact, combined with the response rate, suggests that results of the study can be generalized to the target population.

Instrument

Data describing the 37 participating athletic departments’ strategic planning practices were collected using a questionnaire developed by the author and validated by a panel of experts in strategic planning, higher education, management, and sports management. The reliability of the survey instrument was determined via Cronbach’s alpha (a); all alpha coefficients were within acceptable ranges for comparable instruments (Nunnally, 1967). Coefficients for each subdimension were as follows: general planning factors, a = .67; external factors, a = .89; internal factors, a = .87; constraint factors, a = .82; type of plan factors, a = .74; short- and long-range plans factors, a = .68. A pilot study was also conducted, and recommended improvements were incorporated in the final research instrument.

Results

Data from the survey instrument showed that 75.7% of the responding athletic departments have developed a vision statement, and more than 90% have developed a mission statement, conducted a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis of the internal and external environment, and developed long-range and short-range plans (Table 1). In addition, 73% of the surveyed athletic departments reported that they evaluate the performance of their planning process, while 78.4% reported that they evaluate the performance of the athletic department.

Table 1

Activities Included in Surveyed Athletic Departments’ Current Planning Processes

| Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Vision statement | ||

| Yes | 28 | 75.7 |

| No | 9 | 24.3 |

| Mission statement | ||

| Yes | 35 | 94.6 |

| No | 2 | 5.4 |

| Evaluation of strengths and weaknesses | ||

| Yes | 34 | 91.9 |

| No | 3 | 8.1 |

| Evaluations of opportunities and threats | ||

| Yes | 34 | 91.9 |

| No | 3 | 8.1 |

| Formulation of goals and objectives | ||

| Yes | 35 | 94.6 |

| No | 2 | 5.4 |

| Formulation of long-range plans | ||

| Yes | 35 | 94.6 |

| No | 2 | 5.4 |

| Formulation of short-range plans | ||

| Yes | 35 | 94.6 |

| No | 2 | 5.4 |

| Formulation of planning process | ||

| Yes | 27 | 73 |

| No | 10 | 27 |

| Performance Evaluation | ||

| Yes | 29 | 78.4 |

| No | 8 | 21.6 |

However, the percentage fitting all three criteria specified to indicate authentic strategic planning was smaller, only 59.5% (Table 2). The three criteria are (a) the formalization of long-range written plans; (b) the assessment of the external and internal environments; and (c) the establishment of strategies based on a departmental mission and objectives. The remaining 40.5% of the surveyed athletic departments were identified as nonstrategic planners not meeting the three criteria, although they may have indicated that they did pursue some components of the strategic planning process. Athletic departments in the nonstrategic planner group were excluded from the present analysis, because their planning endeavors represented the use of only short-range written plans and budgets, for the current fiscal period; or the use of only unwritten short-range plans maintained in an administrator’s memory (intuitive planners); or no use of measurable planning procedures at all.

Table 2

Surveyed Athletic Departments’ Level of Planning

| Type of Plan Used | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Structured long-range plan | 22 | 59.5 |

| Operational plan | 11 | 29.7 |

| Intuitive plan | 3 | 8.1 |

| Unstructured plan | 1 | 2.7 |

The study found that at least 50% of the responding athletic departments reported that they weighed three external factors—competition, community opinion, and government legislation—to a “very great or great” extent when formulating their plans (Table 3). In addition, at least 78.3% of the responding athletic departments reported that they weighed three internal factors—financial performance, adequacy of facilities, and department staff performance—to a “very great or great” extent when formulating plans (Table 4). The study also found that at least 75.7% of the responding departments considered financial plans and human resource plans to a “very great or great” extent during their planning activities (Table 5).

Table 3

Frequency and (Percentage) of External Factors Considered to Three Different Extents by Athletic Departments During Plan Formulation, in Descending Order of Consideration

| External Factor | Very Little or Little | Some | Very Great or Great |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competition | 4(10.8) | 10(27.0) | 23(62.1) |

| Community opinion | 7(19.0) | 12(32.4) | 18(48.6) |

| Government legislation | 10(27.0) | 9(24.3) | 18(48.6) |

| Economic/tax | 10(27.0) | 12(32.4) | 15(40.5) |

| BUSA trends | 10(27.0) | 13(35.1) | 14(37.8) |

| Demographic trends | 4(10.8) | 20(54.1) | 13(35.1) |

| Political trends | 17(47.9) | 14(37.8) | 6(16.2) |

| Spectators | 22(59.4) | 14(37.8) | 1(2.8) |

aCorresponding Likert-type scale self-measures: 1 (very little), 2 (little), 3 (some), 4 (great), 5 (very great).

Table 4

Frequency and (Percentage) of Internal Factors Considered to Three Different Extents by Athletic Departments During Planning Process, in Descending Order of Consideration

| Internal Factor | Very Little or Little | Some | Very Great or Great |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial performance | – | 2(5.4) | 35(94.6) |

| Adequacy of facilities | 1(2.7) | 3(8.1) | 33(89.2) |

| Staff performance | 3(8.1) | 5(13.5) | 29(78.3) |

| Athletic performance | 4(10.8) | 12(32.4) | 21(56.7) |

| Coaches’ opinion | 6(16.2) | 16(43.2) | 15(40.5) |

aCorresponding Likert-type scale self-measures: 1 (very little), 2 (little), 3 (some), 4 (great), 5 (very great).

Table 5

Frequency and (Percentage) for Management Factors Incorporated to Three Different Extents by Athletic Departments During Planning Activities, in Descending Order of Consideration

| Management Factor | Very Little or Little | Some | Very Great or Great |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial plan | 2(5.4) | 3(8.1) | 32(86.5) |

| Human resource plan | 3(8.1) | 6(16.2) | 28(75.7) |

| Facilities master plan | 2(5.4) | 10(27.0) | 25(67.5) |

| Marketing plan | 9(24.3) | 11(29.7) | 17(45.9) |

| Contingency plan | 17(45.9) | 13(35.1) | 7(18.9) |

aCorresponding Likert-type scale self-measures: 1 (very little), 2 (little), 3 (some), 4 (great), 5 (very great).

What are the key factors that discourage UK university athletic departments from engaging in strategic planning activities? Insufficient financial resources and time were identified by this study as factors that, to a “very great or great” extent, discourage 35% or more of the athletic departments from engaging in strategic planning activities.

Table 6

Frequency and (Percentage) for Factors Discouraging Athletic Departments from Strategic Planning, to Three Different Extents (in Descending Order of Influence)

| Discouraging Factor | Very Little or Little | Some | Very Great or Great |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient financial resources | 8(21.6) | 12(32.4) | 17(45.9) |

| Insufficient time | 15(40.5) | 9(24.3) | 13(35.1) |

| Insufficient training in planning | 20(54.0) | 12(32.4) | 5(13.5) |

| Inadequate communication | 23(62.1) | 9(24.3) | 5(13.5) |

| Staff’s resistance | 27(72.9) | 5(13.5) | 5(13.5) |

| Lack of a planning policy | 27(72.9) | 5(13.5) | 5(13.5) |

| Planning is not valued | 30(81.1) | 5(13.5) | 2(5.4) |

aCorresponding Likert-type scale self-measures: 1 (very little), 2 (little), 3 (some), 4 (great), 5 (very great).

Both hypotheses tested by the study were supported. Chi-square analysis X2(2, N=37)=2,811, p=0,245 showed that the extent to which an athletic department uses strategic planning is indeed independent of the size of the university. No significant relationship was found between the extent of strategic planning and university size (p = 0.57). Similarly, Chi-square analysis X2(3, N=37)=7,192, p=0,66 showed that the extent to which strategic planning is used by athletic departments is independent of their athletic directors’ backgrounds. No significant relationship was found between the extent of strategic planning and the background of athletic directors (p = 0.35).

Discussion, Implications, Recommendations

In this study of member institutions in the British Universities Sports Association, more than 75% of responding athletic departments indicated that they were involved in such strategic planning activities as developing a vision statement, developing a mission statement, formulating goals and objectives, establishing short- and long-term strategies, and developing plan and performance evaluation procedures. However, only 59.5% of the sample could be classified as practicing authentic strategic planning, defined here as participation in three specific things: the formalizing of long-range written plans, the assessing of the external and internal environments, and the establishing of strategies based on departmental mission and objectives. With more than 40% of the athletic departments practicing either nonstrategic planning or no planning, the need clearly exists to outline formal strategic-planning committees, processes, and systems for these departments’ better management.

According to Harvey (1982), a strategic plan is developed in order to gain or maintain a position of advantage relative to one’s competitors. Following the development of the strategic plan, its implementation becomes critical. The present study did not rigorously assess such implementation, and it remains to be determined whether athletic departments that can be identified as strategic planners are also actual implementers of their strategic plans. Such knowledge would be useful for decisions about committing athletic department resources to reach desired objectives.

The present study did provide evidence that whether and how much a university athletic department engages in strategic planning is unrelated to the size of the university. David (1989) noted that small firms pursue a less formal kind of strategic planning than large firms do. Despite this study’s first hypothesis, then, it was a surprise to this author that large universities’ and small ones’ athletic departments generally pursue strategic planning and a strategic approach to decision making in rather similar fashion.

Evidence was also provided by the study suggesting that the extent of strategic planning carried out by the athletic departments is unrelated to athletic directors’ backgrounds. Some of the athletic directors who participated in the survey had private-sector work experience. Nevertheless, either knowledge of and experience with strategic planning was not transferred to the university environment, or such knowledge and experience had not been a meaningful part of the private-sector background. Failure to transfer knowledge and experience may, however, be attributable in some cases to athletic department decision makers’ lack of access to financial and human resources. Alternatively, it could be that some university administrations do not encourage formulation and implementation of strategic plans.

The findings presented above have implications for the development and use of the strategic planning process in athletic departments. First, since the most significant constraints on strategic planning, according to the survey, were insufficient financial resources and insufficient time, athletic departments need to recognize, and then to remove, these constraints if they are to enjoy the benefits of an implemented strategic plan. Second, if athletic departments are to respond to the scientific literature by accepting strategic planning as an important administrative responsibility, then departments must address a third significant constraint, insufficient training and experience in strategic planning procedures. They can do so by providing staff with strategic-planning educational opportunities. Programs meant to develop skills like human relations, analytical thinking, time management, and participatory decision making can greatly assist athletic departments in preparing to carry out the strategic planning process. In taking these two steps, athletic departments will encourage the perception of strategic planning as one of the primary responsibilities of management—not an auxiliary task.

The literature about strategic planning in intercollegiate athletics remains limited for now, even though interest in the topic appears to be growing. Further studies are needed, and the present study’s findings indicate that some of these future investigations might take up the following:

Three to five years from now, a follow-up study with the same sample of BUSA member institutions should seek out any changes in the way the university athletic departments are using the strategic planning process.

Also, further investigation with the same population might assess the extent of strategic planning from a qualitative perspective, one concerned with data from interviews, observation, and the study of official documents. Through observation and interview, for example, such issues as the membership of a strategic planning committee, the type of data applied to strategic planning, the methods by which those data were obtained, the leadership behavior involved in strategic planning, and resistance encountered to strategic planning could all be addressed in detail. Through study of official documents, researchers might gauge the extent to which documents reflect strategic issues like the assessment of external and internal environments.

Another useful investigation might be the evaluation of the relationship between how extensive the strategic planning activities of an athletic department are and the financial performance or productivity of the department. Such a study would require establishing appropriate measures of financial performance or productivity. An example would be the percentage of self-generated, not university-provided, revenue (e.g., sponsorships, concessions, ticket sales); or alternatively, the national performance of the total athletic program provided by the department.

Finally, future research should be undertaken to establish a valid, reliable strategic planning survey instrument for use in any United Kingdom university athletic department to evaluate the quantity and quality of its ongoing strategic planning activities, as well as the quality of the implementation of strategic plans it has previously developed.

References

Agwu, P. (1992). Strategic planning in higher education: A study of application in Arkansas senior colleges and universities. Dissertation Abstracts International, 53(08), 745A. (UMI No. AAC 9300582)

Ansoff, H. I. (1984). Implanting strategic management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ansoff, H. I., & McDonnell, E. (1990). Implanting strategic management (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bank, B. (1992). Strategic management in nonprofit art organizations: An analysis of current practice. Dissertation Abstracts International, 32(01), 454A. (UMI No. AAC 1353924)

Barry, B. W. (1986). Strategic planning workbook for nonprofit organizations. St. Paul, MN: Amherst H. Wilder Foundation.

British Universities Sports Association. (1999). Report of the working party of the National Competition Sport Committee: Review of sporting offer 1998/9. London.

Bryson, J. M. (1988). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bryson, J. M., Freeman, R. E., & Roering, W. D. (1986). Strategic planning in the public sector: Approaches and directions. In B. Checkoway (Ed.), Strategic perspectives on planning practice (pp.157). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Bryson, J. M., Van de Ven, A. H., & Roering, W. D. (1987). Strategic planning and revitalization of the public service. In R. Denhardt & E. Jennings (Eds.), Toward a new public service (pp. 163). Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

Bucher, C. A. (1987). Management of physical education and athletic programs (9th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Times Mirror/Mosby College.

Busler, B. (1992). The role of strategic planning and its effect on decision making in Wisconsin public schools. Dissertation Abstracts International, 53(07), 514A. (UMI No. AAC 9223867)

Christensen, C., Berg, N., Salter, M., & Stevenson, H. (1985). Policy formulation and administration (8th ed.). Homewood, IL: Irwin.

David, F. (1989). Strategic management. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Duncan, H. (1990). Strategic planning theory today. Optimum: The Journal of Public Sector Management, 20(4), 63–74.

Dyson, D., Manning, M., Sutton, W., & Migliore, H. (1989, May). The effect and usage of strategic planning in intercollegiate athletic departments in American colleges and universities. Paper presented at the meeting of the North American Society for Sport Management, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Elkin, P. M. (2007). Mastering business planning and strategy (2nd ed.). London: Thorogood.

Ensor, R. (1988, September). Writing a strategic sports marketing plan. Athletic Business, p. 48-50.

Espy, S. N. (1988). Creating a firm foundation. Nonprofit World, 6(5), 23–24.

Gerson, R. (1989). Marketing health/fitness services. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Hall, G. (1994). Strategic planning: A case study of behavioral influences in the administrative decisions of middle managers in small independent colleges.

Dissertation Abstracts International, 55(11), 745A. (UMI No. AAC 9510480)

Institute of Leisure and Amenity Management. (1999). Weekly appointments service. London: Ilam services Ltd.

Kotler, P. (1988). Marketing management: Analysis, planning, implementation, and control (6th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kriemadis, A. (1997). Strategic planning in higher education athletic departments. International Journal of Educational Management, 11(6), 238–247.

Kriemadis, A., Emery, P., & Puronaho, K. (2001). Strategic planning in United Kingdom university athletic departments. Proceedings of the European Association for Sport Management, Spain, September.

Laycock, D. K. (1990). Are you ready for strategic planning? Nonprofit World, 8(5), 25–27.

Lubacz, P. (1999). Counting the cost. Durham First, 9. University of Durham.

Medley, G. I. (1988). Strategic planning for the World Wildlife Fund. Long Range Planning, 21(1), 46–54.

Mintzberg, H., Lampel, J., Quinn, J., & Ghoshal, S. (2003). The strategy process: Concepts, contexts, cases (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Nelson, R. S. (1990). Planning by a nonprofit should be very businesslike. Nonprofit World, 8(6), 24–27.

Newman, W. H., & Wallender, H. W. (1987). Managing not-for-profit enterprises. Academy of Management Review, 3(1), 24–31.

Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pearce, J. A., & Robinson, R. D. (1985). Strategic management: Strategy formulation and implementation (2nd ed.). Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Robinson, J. (1992). Strategic planning processes used by not-for-profit community social service organizations and a recommended strategic planning approach. Dissertation Abstracts International, 53(11), 454A. (UMI No. AAC 9302958)

Rowe, A. J., Mason, R. O., Dickel, K. E., & Snyder, N. H. (1989). Strategic management: A methodological approach (3rd ed.). New York: Addison-Wesley.

Smith, C. A. (1985). Strategic planning utilized in Atlantic Coast Conference intercollegiate athletics. Dissertation Abstracts International, 42, 4370–4371A. (UMI No. 50)

Steiner, G. A. (1979). Strategic planning: What every manager must know. New York: Free Press.

Sutton , W. A., & Migliore, H. (1988). Strategic long-range planning for intercollegiate athletic programs. Journal of Applied Research in Coaching and Athletics, 3, 233–261.

Wheelen, T., & Hunger, J. D. (2008). Strategic management and business policy: Concepts and cases (11th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Williams, D. (1992). Perspectives on strategic planning in Durham county schools. Dissertation Abstracts International, 53(07), 51A. (UMI No. AAC 9234929)

Wilson, P. (1990). Strategic planning in the public sector. Practising Manager, 10(2), 23–34.

Wolf, T. (1999). Managing a nonprofit organization in the twenty-first century. New York: Fireside.

Impact of Cold Water Immersion on 5km Racing Performance

Abstract

Much effort over the past 50 years has been devoted to research on training, but little is known about recovery after intense running efforts. Insufficient recovery impedes training and performance. Anecdotal evidence suggests that cold water immersion immediately following intense distance running efforts aids in next day performance perhaps by decreasing injury or increasing recovery. The purpose of this study was to compare 5 km racing performance after 24 hrs with and without cold water immersion. Twelve well-trained runners (9 males, 3 females) completed successive (within 24 hours) 5 km performance trials on two separate occasions. Immediately following the first baseline 5 km trial, runners were treated with ice water immersion for 12 minutes followed by 24 hrs of passive recovery (ICE). Another session involved two 5 km time trials: a baseline trial and another trial after 24 hrs of passive recovery (CON). Treatments occurred in a counterbalanced order and were separated by 6-7 days of normal training. ICE (20:08 ± 2.0 min) was not significantly different (p = 0.09) from baseline (19:59 ± 2.0 min). CON (19:59 ± 1.9 min) was significantly (p = 0.03) slower than baseline (19:49 ± 1.9 min). ICE heart rate (175.3 ± 7.6 b/min) was significantly (p = 0.02) less than baseline (178.3 ± 9.8 b/min), yet CON heart rate (177.3 ± 6.3 b/min) was the same as baseline (177.3 ± 7.3 b/min). ICE rate of perceived exertion (19.2 + 1.0) was significantly less (p = 0.03) than baseline (19.8 ± 0.5) while CON rate of perceived exertion (19.5 ± 0.8) was not significantly different (p = 0.39) from baseline (19.6 ± 0.8). Seven individuals responded negatively to ICE running a mean 24.0 ± 13.9 seconds slower than baseline. Nine individuals responded negatively to CON by running a mean 17.4 ± 12.1 seconds slower than baseline. Three individuals responded positively to ICE running a mean 20.33 ± 6.7 seconds faster during second day performance. Three individuals responded positively to CON by running a mean 13.3 ± 6.8 seconds faster than baseline. In general, cold water immersion minutely reduced the decline of next day performance, yet individual variability existed. Efficacy of longer durations of cold water immersion impact after 48 hrs and on distances greater than 5 km appear to be individual and need to be further explored.

Key words: cryotherapy, ice water immersion, passive recovery, running

Introduction

Recovery from hard running efforts plays a vital role in determining when a runner can run at an intense level again (Fitzgerald, 2007). Hard training, followed by adequate recovery, allows the body to adapt to the unusual stress and become better accustomed and more prepared for the same stress, should it occur again (Fitzgerald, 2007; Sinclair, Olgesby, & Piepenberg, 2003). Balancing hard efforts with periods of rest is essential in improving performance during endurance efforts.

The recovery process from endurance efforts tends to revolve around repairing damaged muscle fibers and replenishing glycogen stores (Gomez et al., 2002; Nicholas et al., 1997). Methods proposed to enhance recovery, such as cold water immersion, potentially decrease swelling and the severity of delayed onset of muscle soreness (DOMS), which possibly benefits endurance (i.e. running) and anaerobic performance (Higdon, 1998; Vaile, Gill, & Blazevich, 2007).

Cold water immersion is a common practice among collegiate and professional athletes following intense physical efforts. Anecdotal evidence from several National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) collegiate head athletic trainers suggests that cooling the legs after a hard training effort may benefit the next day’s performance. Popular running and athletic magazines (e.g., Runner’s World, Running Times, etc.) have continually suggested that applying cold water to the legs of a runner facilitates a better perceived feeling for the next run on the following day. Yet, despite its widespread use there is no scientific data supporting the notion that cooling the legs after a hard distance running effort will improve performance 24 hrs later.

The use of cold as a treatment is as ancient as the practice of medicine, dating back to Hippocrates (Stamford, 1996). The therapeutic use of cold is the most commonly used modality in the acute management of musculoskeletal injuries. Running is a catabolic process, with eccentric muscle contractions leading to muscle damage. Applying cold to an injured site decreases pain sensation, improves the metabolic rate of tissue, and allows uninjured tissue to survive a post-injury period of ischemia, or perhaps allows the tissue to be protected from the damaging enzymatic reactions that may accompany injury (Arnheim and Prentice, 1999; Merrick, Jutte, & Smith, 2003). The use of cryotherapy, between sets of “pulley exercises” (similar to a seated pulley row), decreased the feelings of fatigue of the arm and shoulder muscles of 10 male weight lifters (Verducci, 2000), while other cryotherapy research involving recovery from intense anaerobic efforts has yielded equivocal results (Barnett, 2006; Cheung, Hume, & Maxwell, 2003; Crowe, O’Connor, & Rudd, 2007; Howatson, Gaze, & Van Someren, 2005; Howatson and Van Someren, 2003; Isabell et al., 1992; Paddon-Jones and Quigley, 1997; Sellwood et al., 2007; Vaile, Gill, & Blazevich, 2007; Vaile et al., 2008; Yackzan, Adams, and Francis, 1984). However, methods of cryotherapy effective for enhancing recovery from distance running efforts have not been examined.

Long duration or high intensity running contributes to muscle cell damage (Fitzgerald, 2007; Noakes, 2003). Edema, a by-product of muscle damage can cause reduced range of joint motion. Because cryotherapy has been shown to decrease inflammation (Dolan et al., 1997; O’Conner and Wilder, 2001), it is logical to assume that this treatment may reduce the severity of DOMS. Less pain may permit an athlete to push themselves harder potentially improving performance. Despite the fact that previous research has shown that 24 hrs alone is not sufficient recovery from 5 km running performance (Bosak, Bishop, & Green, 2008), it might be possible that combining cold water immersion with 24 hrs of recovery could potentially hasten the recovery process. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare 5 km racing performance after 24 hrs of passive recovery with and without cold water immersion.

Methods

Participants:

Participants for the study were 12 well trained male (n = 9) and female (n = 3) runners currently engaged in rigorous training. Runners from the local road running and track club, local triathlon competitors, as well as former competitive high school and college runners, were recruited by word of mouth. Participant inclusion criteria included the following: 1) Subjects must have been currently involved in a distance running training program; 2) Their 5 km times previously run had to be at least 16-22 min for male runners or 18-24 min for female runners; 3) They had to be currently averaging at least 20-30 miles (running) per week; 4) They had to have previously completed at least five 5 km road or track races; 5) They had to have a VO2max of at least 45 ml/kg/min (females) or 55 ml/kg/min (males); and 6) They had to provide sufficient data (from running history questionnaires, physical activity readiness questionnaires, and health readiness questionnaires) that reflected good health.

Participants completed a short questionnaire regarding their running background, racing history, and current training mileage. All participants were volunteers and signed a written informed consent outlining requirements as well as potential risks and benefits resulting from participating.

Procedures:

Participants were assessed for age, height, body weight, and body fat percentage using a 3-site skinfold technique (Brozek and Hanschel, 1961; Pollock, Schmidt, & Jackson, 1980). Participants were fitted with a Polar heart rate monitor, and then completed a graded exercise test (GXT) to exhaustion lasting approximately 12-18 min. VO2max, heart rate (HR), and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) were collected every minute.

All GXTs were completed on a Quinton 640 motorized treadmill. The test began with a 2 min warm-up at 2.5 mph. Speed was increased to 5 mph for 2 min, followed by 2 min at 6 mph, 2 min at 7 mph, and 2 min at 7.5 mph. At this point, incline was increased two percent every 2 min thereafter until the participant reached volitional exhaustion (i.e. they felt like they could no longer continue running at the required speed and grade). Once the participant reached volitional exhaustion, they were instructed to cool down until they felt recovered.

Approximately five days later, participants performed their first 5 km race (performance trial) between the hours of 6:30 am to 7:30 am. The time of day for each performance trial was consistent throughout the entire study. All performance trials were completed on a flat hard-surfaced 0.73 mile loop. Prior to each trial, participants completed visual analog scales, before and after a 1.5 mile warm-up run, regarding their feelings of fatigue and soreness within local muscle groups (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius), and for lower and total body muscle groups. Visual analog scales were 15 cm lines, where participants placed an “X” on the line indicating their feelings (with 0 = no fatigue or soreness and 15 = extreme fatigue or soreness). The focus of the visual analog scales was to determine if participants felt the same before the start of every time trial. Participants were also required to rate their perceived exertion (RPE) after the warm-up and prior to the start of each 5 km, during each trial, and at the end of each performance trial to determine if feelings of effort remained consistent between each trial, as well as during each lap and at the end of each trial.

Runners underwent a 1.5 mile warm-up prior to every 5 km performance trial (Kaufmann and Ware, 1977). Participants completed four 5 km performance trials within nine days. Two 5 km performance trials (baseline and CON) were separated by 24 hrs of passive recovery. Passive recovery was deemed as no exercise or extensive physical activity during the allotted recovery hours. Two 5 km performance trials (baseline and ICE) were also separated by 24 hrs of passive recovery, but with 12 minutes of 15.5ºC water immersion immediately following the baseline trial. The two sessions of 5 km performance trials were counterbalanced and were separated by 6-7 days of normal training. Each trial session therefore, had a separate baseline preceded by 24 hrs of passive recovery.

Ideal cryotherapeutic water temperature has not been determined, yet various head collegiate athletic trainers prefer that the water temperature does not dip below 13ºC (55.5ºF) since many people find water temperatures below 13ºC uncomfortable (O’Connor and Wilder, 2001). Also, the duration of ice baths generally lasts 10-15 minutes and is usually applied immediately after a hard training session (Crowe, O’Connor, & Rudd, 2007; Schniepp et al., 2002; Vaile et al., 2008). Hence, in this study, 15.5ºC (60ºF) was the temperature for the cold water and the athletes were immersed for 12 min.

During each time trial, average heart rate and ending RPE were recorded in order to determine if effort for each 5 km was consistent. All participants competed with runners of similar ability to simulate race day and hard training conditions, while verbal encouragement was provided often and equally to each participant. At the end of every performance trial, each runner was instructed to complete a low intensity 1.5 mile cool-down. Each total testing trial required approximately 60 min.

Statistical Analysis:

Basic descriptive statistics were computed. Repeated measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed for making comparisons between CON and baseline and PAS and baseline performance trials for the following variables: finishing times, HR, RPE, and fatigue or soreness responses. All statistical comparisons were made at an a priori p < .05 level of significance. Data were expressed as group mean + standard deviation and individual results.

In order to evaluate individual responses, data from each participant’s first run was compared to the second run using a paired T-test. The least significance group mean difference (p < 0.05) was determined and group mean finishing time was adjusted to determine the amount of change in seconds needed for significance to occur. The time change between the first trial run and the adjusted trial run baseline was divided by the first trial run and expressed as mean number of seconds or percent for both the ICE (9.3 seconds or 0.8%) and CON (9.5 seconds or 0.8%) trials. The percent values were applied to each individual baseline time in order to determine how many seconds (positive or negative) the second performance trial time had to be over or under the first performance trial, in both CON and ICE conditions, to quantify as a response. Participants were then labeled as non-responders, positive-responders (faster after treatment), and negative-responders (slower after treatment).

Results

Descriptive characteristics are found in Table 1. The participants were between the ages of 18 and 35 (the majority of subjects were between ages 20-28) years. All participants were trained runners or triathletes (where running was their specialty event).

Mean finishing times, HR, and RPE for CON and ICE trials are found in Table 2. CON was significantly (p = 0.03) slower (10 seconds) than baseline, where as ICE was not significantly different (p = 0.09) from baseline. No significant differences were found between CON HR vs. baseline, but ICE HR was significantly (p = 0.01) less than baseline. No significant differences (p = 0.39) were found between CON RPE and baseline, yet ICE RPE was significantly (p = 0.03) less than baseline.

Figure 1 shows individual changes in finishing times for all CON and ICE performance trials. To be considered a non-responder, the individual time change had to fall within 0.8% of baseline performance for ICE and CON. Positive and negative responders (Table 3) were identified when individual time change was greater than 0.8% for CON and ICE trials, with a positive responder being one whose second performance trial time improved (expressed as a negative value) and a negative responder being one whose second performance trial time slowed (expressed as a positive value).

Seven individuals responded negatively to ICE by running a mean 24.0 ± 13.9 seconds slower during the second trial (Table 3). Three individuals responded positively to ICE by running a mean 20.3 ± 6.7 seconds faster than baseline. Two individuals were considered non-responders to ICE with a mean time change of 2.5 ± 0.7secs.

Seven individuals responded negatively to CON by running a mean 20.6 ± 9.0 seconds slower than baseline (Table 3). Three individuals responded positively to CON by running a mean 13.3 ± 6.8 seconds faster than baseline. Two individuals were non-responders to the CON trials with a mean time change of 6.5 ± 0.7 seconds. It is important to note that the seven individuals who were negative responders to ICE were not the same seven participants who responded negatively to CON. Also, the three participants who responded positively to ICE were not the same three individuals who responded positively to CON. Finally, the non-responders to ICE were not the same non-responders to CON.

Soreness and fatigue scores (Table 4) on the pre-and post-warm-up fatigue or soreness visual analog scales were not significantly different between CON and baseline versus ICE and baseline.

Discussion

The effects of cold-water immersion on recovery and next day performance in 5 km racing have not been previously evaluated. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to compare 5 km running performance after 24 hrs of passive recovery with and without cold water immersion. This study appeared to indicate that cold water immersion does not dramatically help performance (regarding the group of runners as a whole) during second day 5 km trials.

Twenty-four hours of passive recovery may allow for normalization of muscle and liver glycogen, yet muscle function and performance measures may not be fully recovered (Foss and Keteyian, 1998). Hence, 24 hrs of recovery, by itself, may not be sufficient to allow for a return to optimal performance (Bosak, Bishop, & Green, 2008). When racing (e.g., a 5 km distance) on consecutive days, race times may be slower on the second day due to magnified perception of pain and impaired muscle function associated with DOMS (Brown and Henderson, 2002; Fitzgerald, 2007; Galloway, 1984). Since cold water immersion may speed up the recovery process (Arnheim and Prentice, 1999; Vaile et al., 2008) it is logical to assume that cold water immersion immediately after a 5 km race or workout could attenuate soreness potentially minimizing performance decrements on successive days.

There were no significant (p = 0.09) differences in 5 km performance between ICE and baseline, indicating that mean performance during ICE was not significantly slower (9 seconds) than baseline (refer to Table 2). However, CON performance was significantly (p = 0.03) slower (10 seconds) than baseline. Hence, due to significant differences occurring between ICE and baseline, it appears that cold water immersion slightly attenuated the rate of decline on successive 5 km time trial performance. However, the time difference between CON and baseline versus ICE and baseline was a mere second. Therefore, from a practical standpoint, cold water immersion was no more beneficial than CON on successive 5 km performance.

Despite the minimal differences between CON (10 seconds) and ICE (9 seconds) trials regarding mean time change, it is important to focus on the effects of cold water immersion on individual runners (Figure 1). Because some runners ran slower during successive performance trials while other runners ran faster, the mean finishing times do not necessarily give a true impression of the benefits or liabilities of the specific treatments involved in this study. As it is with most ergogenic aids, individual variability suggests what works (e.g., ice) for one person may not work the same for another person. It is possible that the treatment may often not have an effect at all, as similar to what occurred with several prior anaerobic performance studies (Barnett, 2006; Cheung, Hume, & Maxwell, 2003; Crowe, O’Connor, & Rudd, 2007; Howatson, Gaze, & Van Someren, 2005; Howatson and Van Someren, 2003; Isabell et al., 1992; Paddon-Jones and Quigley, 1997; Sellwood et al., 2007; Vaile et al., 2008), which was also the case in this study as two individuals were considered non-responders to ICE with a mean time change of 2.5 ± 0.7 seconds between ICE and baseline, while two other participants were non-responders to CON with a mean time change of 6.5 ± 0.7 seconds between CON and baseline.

Three individuals responded positively (Table 3) to ICE, running a mean 20.33 ± 6.7 seconds faster, indicating that cold water immersion may have actually allowed these individuals to run faster on the second day. However, 3 different individuals responded positively to CON, running a mean 13.3 ± 6.8 seconds faster than baseline. The mechanism by which cold water immersion aids in recovery, from endurance performance, remains somewhat unclear and equivocal (Schniepp et al., 2002; Vaile et al., 2008). Yet, several runners who did run faster during ICE trial, verbally indicated that prior to the second trial, their legs felt better (regarding fatigue and soreness) than they had prior to CON. Thus, the notion of feeling better may have allowed the runners to perform faster.

Seven individuals responded negatively (Table 3) to ICE, running a mean 24.0 ± 13.9 seconds slower. However, they were not the same seven individuals who responded negatively to CON, who ran an average of 20.6 ± 9.0 seconds slower than baseline. As was the case with Schniepp et al. (2002) endurance cycling recovery study and various anaerobic performance studies (Crowe, O’Connor, & Rudd, 2007; Sellwood et al., 2002; Vaile et al., 2008; Yackzan, Adams, & Francis, 1984), it appears ICE may have had a more negative effect, for these individuals, on second day performance compared to CON.

Three individuals responded positively to CON running a mean 13.3 ± 6.8 seconds faster during the second day performance trial. It is unclear why some participants ran faster during CON. There were no consistent patterns of HR and increased or decreased performance with all participants during all CON and ICE trials. As a group, no significant differences were found between CON vs. baseline, regarding HR (p = 1.00) and RPE (p = 0.39), despite significant differences (p = 0.04) occurring in mean finishing time. However, mean finishing times for ICE were similar, yet significant differences were found between ICE vs. baseline for both HR (p = 0.01) and RPE (p = 0.03). Hence, there does not appear to be a consistent pattern between performance times and HR and/or RPE.

It can be assumed that a lower HR may be associated with slower times, since HR and intensity levels tend to be linearly related. However, only participants 1, 5, and 6 consistently ran slower during both CON and ICE second day performances with lower HR during both trials. During the ICE trials, only participants 1, 5, 6, and 9 ran slower and had a lower HR. During the CON trials, only 1, 3, 5, 6, ran slower and had a lower HR. Also, soreness and fatigue scores (Table 4) on the pre and post warm-up fatigue or soreness visual analog scales were not significantly different between CON and baseline versus ICE and baseline. These results indicate that all runners tended to feel the same prior to each second day 5 km trial. Therefore, since inconsistencies exist between HR and performance trials and no significant differences were found regarding RPE and fatigue or soreness visual analog scales, it is assumed that each participant completed each trial with similar effort.

Conclusion

The current findings of this study suggest that cold water immersion does not sufficiently enhance recovery (specifically regarding the group of runners as a whole). However, three runners benefited from cold water immersion. Hence, what works for one person may not work for another person. Thus, it may be beneficial for runners to undergo this protocol in order to see which type of recovery method improves their recovery process. Secondly, the results of the study may give credence to some runners’ perception of feeling better due to cold water immersion after a hard running effort. However, one should remember that individual variability existed in response to treatment (ice immersion) within the current study. Future research is needed to see if a greater length of time or slightly lower water temperature in cold water immersion will decrease the rate of decline more or if the effects of cold water immersion are even more predominant on second day performance of distances greater than 5 km.

References

Arnheim, D. D., & Prentice, W. E. (1999). Essentials of athletic training (4th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Barnett, A. (2006). Using recovery modalities between training sessions in elite athletes: Does it help? Sports Medicine, 36 (9), 781-796.

Bosak, A., Bishop, P., & Green, M. (2008). Comparison of 5km racing performance after 24 and 72 hours of passive recovery. International Journal of Coaching Science (In Review).

Brown, R. L., & Henderson, J. (2002). Fitness Running (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Brozek, J., & Hanschel, A. (1961). Techniques for measuring body composition. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

Cheung, K., Hume, P., & Maxwell, L. (2003). Delayed onset muscle soreness: treatment strategies and performance factors. Sports Medicine, 33 (2), 145-164.

Crowe, M. J., O’Connor, D., & Rudd, D. (2007). Cold water recovery reduces anaerobic performance. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 28 (12), 994-998.

Dolan, M. G., Thorton, R. M., Fish, D. R., & Mendel, F. C. (1997). Effects of cold water immersion on edema formation after blunt injury to the hind limbs of rats. The Journal of Athletic Training, 32, 233-238.

Fitzgerald, M. (2007). Brain Training for Runners. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Foss, M. L., & Keteyian, S. J. (1998). Fox’s Physiological Basis for Exercise and Sport. Ann Arbor, MI: McGraw-Hill.

Galloway, J. (1984). Galloway’s Book on Running. Bolinas, CA: Shelter Publications.

Gomez, A. L., Radzwich, R. J., Denegar, C. R., Volek, J. S., Rubin, M. R., Bush, J.A., Doan, B.K., et.al. (2002). The effects of a 10-kilometer run on muscle strength and power. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 16, 184-191.

Higdon, H. (1998). Smart Running. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press Inc.

Howatson, G., Gaze, D., & Van Someren, K. A. (2005). The efficacy of ice massage in the treatment of exercise-induced muscle damage. The Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 2005, 15 (6), 416-422.

Howatson, G. & Van Someren, K. A. (2003). Ice massage: Effects on exercise-induced muscle damage. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 43 (4), 500-505.

Isabell, W. K., Durrant, E., Myrer, W., & Anderson, S. (1992). The effects of ice massage, ice massage with exercise, and exercise on the prevention and treatment of Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness. The Journal of Athletic Training, 27 (3), 208-217.

Kaufmann, D. A. & Ware, W. B. (1977). Effect of warm-up and recovery techniques on repeated running endurance. The Research Quarterly, 2, 328-332.

Merrick, M. A., Jutte, L. S., & Smith, M. E. (2003). Cold modalities with different thermodynamic properties produce different surface and intramuscular temperatures. Journal of Athletic Training, 38, 28-35.

Nicholas, C. W., Green, P. A., Hawkins, R. D., & Williams, C. (1997). Carbohydrate intake and recovery of intermittent running capacity. International Journal of Sport Nutrition, 7, 251-260.

Noakes, T. (2003). Lore of Running (4th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

O’Conner, F. G., & Wilder, R. P. (2001). Textbook of Running Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Paddon-Jones, D. J., & Quigley, B. M. (1997). Effects of cryotherapy on muscle soreness and strength following eccentric exercise. The International Journal of Sports Medicine, 18 (8), 588-593.

Pollock, M. L., Schmidt, D. H., & Jackson, A. S. (1980). Measurement of cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition in the clinical setting. Comprehensive Therapy, 6, 12-27.

Schniepp, J., Campbell, T. S., Powell, K. L., & Pincivero, D. M. (2002). The effects of cold water immersion on power output and heart rate in elite cyclists. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 16 (4), 561-566.

Sellwood, K. L., Bruker, P., Williams, D., Nicol, A., & Hinman, R. (2007). Ice-water immersion and delayed-onset muscle soreness: a randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41 (6), 392-397.

Sinclair, J., Olgesby, K., & Piepenburg, C. (2003). Training to Achieve Peak Running Performance. Boulder, CO: Road Runner Sports Inc.

Stamford, B., Giving injuries the cold treatment. (1996). The Physician and Sports Medicine, 23, 1-4.

Vaile, J., Gill, N. D., & Blazevich, A. J. (2007). The effect of contrast water therapy on symptoms of delayed onset of muscle soreness. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21 (3), 697-702.

Vaile, J., Halson, S., Gill, N., & Dawson, B. (2008). Effect of hydrotherapy on recovery from fatigue. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 29 (7), 5:39-544.

Vaile, J., Halson, S., Gill, N., & Dawson, B. (2008). Effect of hydrotherapy on the signs and symptoms of delayed onset muscle soreness. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 102(4), 447-455.

Verducci, F. M. (2000). Interval cryotherapy decreases fatigue during repeated weight lifting. The Journal of Athletic Training, 35, 422-426.

Yackzan, L., Adams, C., & Francis, K. T. (1984). The effects of ice massage on delayed muscle soreness. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 12 (2), 159-165.

Appendices

Implementing a Breathing Technique to Manage Performance Anxiety in Softball

Submitted by: Linda Garza, MS – Purdue University and Sally J. Ford, PhD – Texas Woman’s University

Abstract

An intervention strategy was developed, implemented, and evaluated that aimed at minimizing performance anxiety. The goal was to guide NCAA Division I softball athletes in using a breathing technique that, by contributing to the management of performance anxiety, would help each athlete reach full potential on the softball field. The strategy focused on the effects of the breathing technique on the participants’ heart rates, in relation to daily anxiety events; a heart rate monitor and anxiety logs were used to obtain data. All 4 of the athletes studied indicated improvement at various stages in the program.

(more…)

Is That a Real LeBron Ball? RFID and Sports Memorabilia

Submitted by: David C. Wyld – Southeastern Louisiana University

Abstract

The sports memorabilia marketplace today is a multibillion-dollar, global market. However, it is fraught with hazards, due to the large percentage of counterfeit memorabilia, which some estimates peg at 90% of all items on the market. This article overviews the sports memorabilia market and the growing problem of counterfeit items. Then, it examines the prospect for radio frequency identification (RFID) to be used to provide a verifiable chain of custody for articles of sports memorabilia – from the point the item is signed through all subsequent transfers. The article concludes with an analysis of the implications of the introduction of such track and trace authentication technology into this fragmented marketplace and the benefits for all parties involved in sports collectibles.

Keywords: radio frequency identification, chain of custody, authentication, sports memorabilia

Introduction

Autograph seekers. They are a part of every professional – and often amateur – athlete’s life. They are a fixture at sports teams’ training camps, host hotels and stadiums, and anywhere these signature collectors know that athletes will have to pass through on their way to or from an event. They also are a part of the well-known athlete’s every move, as autograph seekers can make it uncomfortable, even impossible, for athletes and their families to enjoy a meal in public or a trip to an amusement park. Many of these autograph hunters are kids, looking to get that one autograph of the professional baseball or football star they admire–the one whose poster they have hanging over their bed. Some of the signature hounds are adults, looking to have literally any athlete they can find sign any team item such as a ball, a bat, a helmet, a jersey, a game program, or so forth, in order to turn an ordinary item into a collectible.

The motivation of many of these autograph seekers is indeed innocent, hoping to have a memento of their favorite athlete or sports team for their wall or mantle. The kid who admires his or her favorite sports star, whether it’s Tiger Woods, Brett Favre, Kobe Bryant, Alex Rodriguez, or David Beckham, can have a lasting memory not just from the signed item but from their brief encounter with a sports legend. All too often however, the motive for the autograph seeker is money. Indeed, the chance is there to cash-in on an athlete’s celebrity, and the players and their teams know it. The worst of the lot are grown-ups who hire children to seek out star’s autographs on a paid basis; they work on the premise that the “cute kid factor” might entice the sports star to stop and sign an item for a 9-year-old child that they wouldn’t for a 40-year-old man. As Baseball Hall of Famer Robin Yount commented, “There is money to be made out there on autographs, (and) you see more people doing it these days for that reason — the business end of it” (Olson, 2006, n.p.).

Yet, the real truth of the matter is that while a signed article can be a point of personal pride, even perhaps a family heirloom, the actual value of the item to knowledgeable sports memorabilia collectors is very limited. That is because of the need to provide verifiable proof of the autographed item’s authenticity. Yes, you may have been at the New Orleans Saints’ training camp in Jackson, Mississippi (as my sons and I were this past summer) and personally witnessed star running back Reggie Bush autograph a football. However, if you were to want to sell the ball, as opposed to displaying it on a shelf in your son’s room, there’s no irrefutable proof that could assure the first buyer, let alone subsequent buyers in the future, as to the validity of Bush’s signature. Not that this stops autograph seekers from trying day after day to get that elusive personalization of basketballs by LeBron James, footballs by Peyton Manning, baseballs by Derek Jeter, and item after item by a myriad of stars. So disruptive to athlete’s lives are some autograph hounds that teams today commonly limit access to their players, not just out of concern for their economic well-being but for their physical safety as well (Maske and Lee, 2007). And, some athletes, such as Michael Jordan, make it publicly known that they will not sign an autograph except through the special events (and often private signing days) for agencies they have contracted with to represent them in what has become an increasingly lucrative market for athletes, supplementing, or even exceeding, what they make on the field by simply signing their names (Johns, n.d.; Fisher, 2000).

The sports memorabilia market today is a global marketplace, estimated to generate revenues in excess of $5 billion annually (Friess, 2007). Items of sports memorabilia are sold in a variety of venues, including physical and online stores, shows and auctions, and in private sales (Smith, n.d.). Small, independent “mom and pop” sports memorabilia stores were once a staple of strip malls across America. According to industry observers, the number of such stores has plummeted from approximately 4,700 a decade ago to just over a thousand today (Keteyian, 2006). Much of this decline can be traced to the shifting of buying and selling sports memorabilia to eBay and other major online auction sites, much as has occurred with other collectibles, such as coins, stamps and antique items (National Auctioneers Association, 2008). However, the ease of access and widening of the marketplace has fostered an explosion of online memorabilia sales. One can see evidence of this by punching in any well-known athlete’s name on eBay, and whether you search for David Beckham, Muhammad Ali, Tiger Woods, or even a lesser known star, you will come-up with dozens, even hundreds, of autographed items up for sale at any given time.

However, the move to greater online sales has only worsened the problem with counterfeit sports memorabilia (Van Riper, 2007). Indeed, it is a market unlike any other, due to the giant presence of counterfeit items. In fact, one law enforcement official described the sports memorabilia market today as being “like the Wild, Wild West” (Keteyian, 2006). Market analyst Havoscope (2008) has concluded that over half of the sports memorabilia market is comprised of counterfeit items. The official estimate from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is that 70% of all signed sports collectibles on the market in the U.S. are counterfeit (Fisher, 2000); forged signatures on items which themselves may or may not be what they are purported to be (after all, even official merchandise from sports leagues and special events, such as Super Bowls, World Cups, or World Series, can be faked). Industry observers believe the true figure to be even higher, ranging to upwards of 90% of all sports collectibles (Prova Group, 2006)! Thus, this is perhaps the ultimate example of a caveat emptor (buyer beware) market.

Anyone can buy a piece of sports memorabilia to hang on the wall or show in a display case, and, if you’re happy with the price you paid for it, all the better. However, unless you personally witnessed the athlete signing the football or the baseball bat, the odds are that the item is not worth any more than what you would have paid for an unsigned version at a local sporting goods store. Thus, there is a great need to have a solution that can assure buyers and sellers of the authenticity of an item, not just presently, but into the future. As we will examine, the certification process today itself is problematic and only contributes to the problem.

For the first time, the advent of radio frequency identification (RFID) technology provides an opportunity for the sports memorabilia marketplace to have the ability for buyers and sellers alike to rely upon a readily accessible and verifiable “chain of custody” for autographed items from the time they are signed by the athlete through all subsequent sales and transfers. In doing so, trust can be built into what has historically been an untrustworthy marketplace, assuring confidence and supporting the genuineness and value of items of sports memorabilia. The author presents both an overview of the sports memorabilia marketplace and RFID technology and follows up with a look at how RFID is being used today to authenticate and to track autographed items of all forms. The article concludes with a look ahead at the implications of the introduction of this new technology and a discussion of what lies ahead.

The Sports Memorabilia Market

A baseball is just a ball until it is signed by a star player. A jersey is just a big shirt until it is worn by an all-star. Then, such items are worth a lot of money, right? Oh, that it were that simple. The terms sports memorabilia and sports collectibles are all too often used interchangeably in the marketplace. According to the recent publication, A Comprehensive Guide to Collecting Sports Memorabilia, the two terms can be differentiated in the following manner: “Photos, cards, jerseys or related sports equipment that have been signed by an athlete are considered memorabilia when that signature has been certified by a reputable distributor. Replica and authentic sports products that are unsigned, or are signed but not authenticated, are considered collectibles” (SportsMemorabilia.com, 2008, n.p., emphasis in the original).

The sports memorabilia market can be segmented into two very distinct segments: trusted sources and other. Trusted sources include both sports memorabilia shows and sports marketing agencies (Fisher, 2000). In the former category, there are a growing number of such events, where athletes are available, generally on a paid basis, to sign a limited number of items, both brought in by fans and bought at the show. At these shows, items are signed, with witnesses present and able to authenticate the athlete’s signature on a certificate of authenticity (COA). This certification is what raises the status and value of an item from being a sports collectible to becoming an item of sports memorabilia (Branton, 2008). The second trusted source is the sports agencies that contract with athletes to be exclusive purveyors of their autographed merchandise. In the United States, the market leaders are companies such as the following:

- ALL Authentic (http://www.allauthentic.com/)

- Mounted Memories (http://www.mountedmemories.com/)

- Steiner Sports (http://www.steinersports.com/)

- Upper Deck (http://www.upperdeck.com/) (Johns, n.d.).

Take Upper Deck for instance. This sports marketing agency has multi-million dollar contracts with current and former athletes from a whole host of sports, including basketball (NBA players Michael Jordan, LeBron James, Kobe Bryant, Dwight Howard, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Magic Johnson), baseball (Albert Pujols, Ken Griffey Jr., Cal Ripken Jr., Sandy Koufax, Nolan Ryan, and Stan Musial), football (Peyton Manning, Tom Brady, Tony Romo, Troy Aikman, John Elway, and Joe Montana), and golf (Tiger Woods and Jack Nicklaus). Upper Deck is a market leader not just because of its status as the exclusive retailer for these star athletes of today and yesterday, but also for its 5-step certification process that stamps the item with a unique hologram and provides the owner with a certificate of authenticity and registration with the Upper Deck database. The company is even using with what it calls its PenCam™ technology, which the company had the misfortune to launch on September 11, 2001 (Henninger, 2002). The PenCam provides further authentication assurance by providing a video capture from–you guessed it–a pen equipped with a tiny video camera that captures the actual signature of the athlete on the item as it is being rendered, which is then recorded and accessible on the company’s database (The Upper Deck Company, 2008).

Items from trusted agencies do command premium prices, due to the fact that buyers and sellers alike have a very reliable chain of custody for their items of sports memorabilia. However, the vast majority of the sports memorabilia market is a murky, “other” place. In most cases, both offline and online, it is a very untrustworthy market, filled with intentionally counterfeited signed sports paraphernalia and fake items that are being bought and sold by mostly unknowing participants (SportsMemorabilia.com, 2008).

The entire sports memorabilia market in the U.S., and indeed around the world, is still reeling from the 2001 bust of a major fraud ring. In Operation Bullpen, the FBI arrested almost two dozen individuals, most of which served prison time for their involvement in the counterfeit sports memorabilia scheme. The enterprise, which operated across more than a dozen states, had expert forgers who could quickly produce entire lots of phony memorabilia. The 2001 raid yielded thousands of fraudulently signed baseballs, jerseys, helmets, photos, and other articles. The damage however, had already been done, and it continues to this day. In all, the FBI estimates that over $100 million in fake memorabilia was sold through the scheme, much of which is still on the market today, being traded by often-unsuspecting buyers and even sellers. The FBI found that not only could the forgers create knock-offs that could fool even the most knowledgeable sports memorabilia authenticator or collector, they uncovered that the criminals had turned the authentication process to their advantage. This is because the crooks were equally adept at falsifying the COAs and holograms put in place in the industry to assure the genuineness of the items (Nelson, 2006).

While 2001s Operation Bullpen was the largest fraud scheme uncovered in the sports memorabilia market to date, criminal arrests continue to plague the industry, with several cases reported in 2008 (Coen, 2008). The FBI estimates that such fraud makes for over a half a billion dollars in annual losses, impacting thousands of customers, and making it more difficult both for athletes to retain the value of their names and for legitimate firms to compete in a skeptical marketplace (Smith, n.d.; Johns, n.d.).

One of the major problem points for the whole memorabilia sales and trading process is the certificate of authenticity that accompanies an item. Ostensibly in place to provide a potential buyer with the assurance that the item he or she is considering purchasing is a genuine article, but today, the effect is almost the opposite. This is because of rampant fraud in the creation of these COAs. Today, there is no industry standard for certification process or for the paper COA itself. Thus, there are rampant problems with these documents. Some fraudulent memorabilia sellers create their own fake COAs to accompany their fake items (SportsMemorabilia.com, 2008; Smith, n.d.; Johns, n.d.). While there are several reputable third-party certification services, who will analyze an item and its history to determine its authenticity, there are also disreputable ones, known to certify, in the words of one law enforcement official, “almost anything” (Franks, 2006).

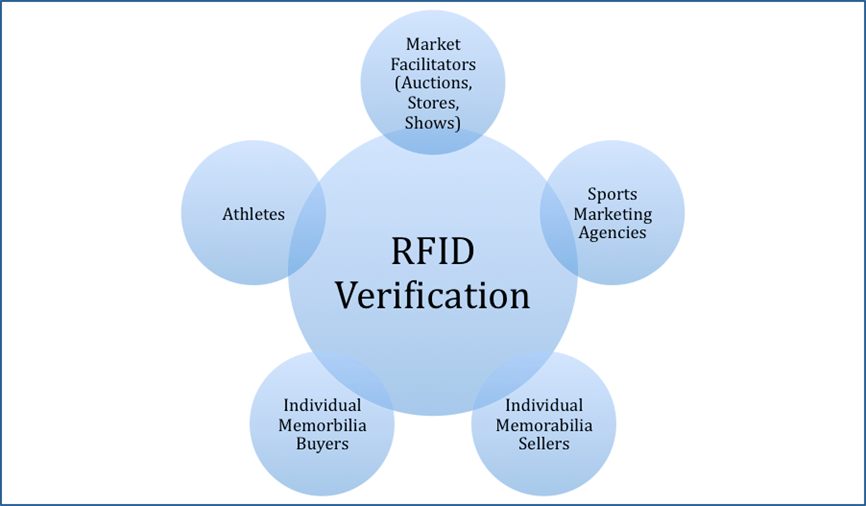

What is clearly needed today is a true chain of custody capability to authenticate items of sports memorabilia from the athlete’s signature through all future trades of the article. With the rampant fraud issues, which can only be exacerbated by both the high dollars attached to many athletes’ items and the accelerating technology that can be used to create both forged articles and proofs of authenticity, there is certainly a common interest for memorabilia collectors, athletes, sports marketing agencies, and the stores, shows and auctions (both online and offline) where the items are bought and sold to develop, for lack of a better term, a fool-proof solution. RFID presents the prospect for just such an incontrovertible chain of custody solution for this marketplace.

Radio Frequency Identification (RFID)

Conceptually, RFID is quite similar to the venerable bar code. Both are automatic identification technologies intended to provide rapid and reliable item identification and tracking capabilities. The primary difference between the two technologies is the way in which they read objects. With bar coding, the reading device scans a printed label with optical laser or imaging technology. However, with RFID, the reading device scans, or interrogates, a small electronic tag or label using radio frequency signals. The specific differences between bar code technology and RFID are summarized in Table 1. There are five primary advantages that RFID has over bar codes. These are as follows:

- Each RFID tag can have a unique code that ultimately allows every tagged item to be individually accounted for.

- RFID allows for information to be read by radio waves from a tag, without requiring line of sight scanning or human intervention.

- RFID allows for virtually simultaneous and instantaneous reading of multiple tags.

- RFID tags can hold far greater amounts of information, which can be updated.

- RFID tags are far more durable. (Wyld, 2005)

Table 1

RFID and Bar Codes Compared