Authors: Jeff Segrave, Tim Spenser, and Kevin Santos

Corresponding Author:

Jeffrey O. Segrave, PhD

Department of Health and Human Physiological Sciences

Skidmore College

Saratoga Springs, NY 12966

[email protected]

518-580-5388

Jeff Segrave is professor of health and human physiological sciences at Skidmore College, Saratoga Spring, New York, USA.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to offer a case study of Pep Guardiola and Manchester City’s 2017-2018 historic season. More specifically, the paper examines how, from a tactical perspective, the Premier League became suited to Pep’s style and leadership, prior to and upon his arrival, analyzes the tactical framework of City’s style of play, and looks at the players who realized Pep’s philosophy. When analyzing Pep’s system and style of coaching, we look at positionality of possession with purpose, aspects of distribution, and transitioning and pressing.

Keywords: Guardiola, Coaching, Manchester City, Premiere League

INTRODUCTION

Manchester City ran rampant during the 2017-2018 season, charging to a Premier League title in historic fashion. A club that has never been strapped for money, City have invariably struggled to find an enduring footballing identity. That was before Pep Guardiola took over at the start of the 2016-2017 season. Since the arrival of the former Barcelona and Bayern Munich manager, Manchester City’s footballing identity has become grounded in the principles of Pep himself. Although his first campaign did not lead to silverware or the type of footballing consistency Pep’s previous sides have shown, the 2017-2018 season did. Not only did City win the 2017-2018 title but they did so in a way that left the media full of praise for Pep, his star players and their wonderful attacking football.

The purpose of this paper is to offer a case study of Pep Guardiola and Manchester City’s 2017-2018 historic season. More specifically, we will examine how, from a tactical perspective, the Premier League became suited to Pep’s style and leadership, prior to and upon his arrival, analyze the tactical framework of City’s style of play, and look at the players who realized Pep’s philosophy.

Tactical History of the Premier League

Football, like technology and science, has always been subject to periods of rapid advancement, and often to equally rapid periods of regression. A game that was once centered mainly on the physical qualities of players, the turn of the 21st century saw the rise of technical football and the emergence of increasingly intelligent players who reveled in the spotlight. Pep is an innovator who before becoming Manchester City’s manager in 2016 dominated the football world for seven years as coach of Barcelona and Bayern Munich, winning 22 trophies along the way. His tactical philosophy and management style clearly shifted the narrative of tactical development and his influence on football worldwide is undeniable. Pep, a technically astute holding midfielder for Barcelona as a player, was raised on the concept of Total Football. The culture of possession football, players being held responsible for all phases of play, and playing aesthetically appealing football with a purpose, were ingrained in Pep from a young age. By 2016, the stage was perfectly set for Pep to make his long awaited entrance into English football. The Premier League was once dominated by a 4-4-2 system, hard work, and extreme role specialization. But, by the time Pep arrived, players were expected to be multifaceted, able to influence every phase of the game. From 1992-2016, the Premier League evolved significantly, partially because of Pep’s success and methods while coaching at Barcelona, but for other reasons as well, all of which presaged Pep’s tenure at Manchester City.

Pep’s tactical foundation is centered on a fluid 4-3-3 that works to dominate possession and press with ferocious pace. This is a massive shift from the previous generation of top Premier League sides. “In the 1990’s, the primary instinct was to get the ball out of the midfield zone,” writes Michael Cox. “In the 2000’s, it was all about keeping it there” (Cox, 2017, 251). Arsenal manager Arsene Wenger is mainly credited for restructuring the culture of coaching in England’s top division in the early 2000’s with his focus on attractive possession football, creative expression, and diligent player health management. Previously, the English game emphasized pumping long balls into dangerous areas, outworking the opposition physically, and grinding out 1-0 victories. Arsenal’s success, coupled with a magnificent 2002 World Cup performance from winners, Brazil, highlighted technical superiority and creativity, which helped to legitimize the idea of fluid tactics and individual player expression. Traditionally, 4-4-2 was the formation that ruled supreme, featuring full backs that sat back and defended, one box to box center mid and one defensive minded center mid, wide mids that got down the line, and two strikers. The two strikers usually featured a target man, whose job was to win headers and rough up the opposition’s defense, and a combination small forward (Cox, 2017, 163).

The first shift away from 4-4-2 came when Manchester United signed Ruud Van Nistelrooy, one of the most proficient finishers the Premier League has ever seen. Manager Sir Alex Ferguson, the most successful manager in League history, changed his formation to emphasize midfield domination, a concept which had never before seemed necessary. Instead of forcing the ball into dangerous positions, Sir Alex began to emphasis the idea of winning the midfield battle in order to maximize the time his side had the ball (Cox, 2017, 168). It was also a Sir Alex signing, defender Rio Ferdinand, that signaled a shift in what was expected of central defenders. Instead of only being expected to tackle, intercept and protect the goal, Ferdinand, and his technical abilities, changed expectations for center backs. This was a major shift in English football, a change to a culture which promoted and emphasized defender contributions to the attacking phase of play. Ferdinand was “the first central defender in English football whose major weakness was defending… his actual passing ability wasn’t particularly outstanding; it was about his calmness in possession” (Cox, 2017, 187). Ferdinand was tasked with dribbling into the midfield to drag the opposition’s higher midfielder out of position and then pass past him. The idea of a defender contributing to attacking phases of play was further personified in the figure of Ashley Cole at Arsenal. A left winger turned left back by Arsene Wenger, Cole was encouraged to push forward to become a vital attacking weapon creating two versus one situations out wide. The player mold of Cole and Ferdinand, which was revolutionary in the early 2000’s, became a major feature of Pep’s Manchester City side in which John Stones and Kyle Walker, well rounded footballers, were changed into defenders.

Yet it was the signing of Claude Makelele in 2003 by Chelsea, coupled with new manager Jose Mourinho’s installment of the 4-3-3, which really began to mold the Premier League into a place that would suit Pep’s innovative spirit. While attacking football was on the rise, the signing of Makelele changed the perception of the abilities that midfielders were expected to possess. Mourinho explained what the Makelele role offered his side during his first year in charge at Chelsea: “Look, if I have a triangle in midfield- Claude Makelele behind and two others just in front- I will always have an advantage against a pure 4-4-2 where the central midfielders are side by side. That’s because I will always have an extra man. It starts with Makelele, who is between the lines” (Cox, 2017, 205). This was Pep’s role at Barcelona, as Spanish football has always placed value on winning the possession and midfield battles. But Pep the player was a deep lying playmaker, while Makelele was the Premier League’s first dominant holding midfielder who was tasked with breaking up play and distributing the ball as quickly and simply as possible to his more attack minded teammates, a role which transformed the distribution and culture of midfield pairings in England. Because Makelele would sit right in front of the back four, other central midfielders, Frank Lampard and Michael Essien, were able to play attacking and box to box roles respectively (Cox, 2017, 209).

The Makelele role brought a balance to the midfield unit that revolutionized Premier League tactics as numerous top teams attempted to find their own holding midfielder to pull the strings. What followed was a host of attack-minded central midfielders whose game focused on passing and emphasized dropping into a holding midfield role to win the ever growing possession battle. Midfield balance is something Pep’s Manchester City side has mastered this season, highlighting the importance of getting the variation of the midfield three correct. With David Silva and Kevin De Bruyne playing deeper than usual in central roles and with Fernandinho sitting behind them, City win the center of the park in most games due to Fernandinho’s ability to sacrifice for the team, break up play, and quickly find two of the most creative players in Premier League history, who are positioned in advanced central roles.

Foreign influence has been essential to tactical growth and innovation in the Premier League. In 2009 and in 2011, Barcelona comfortably beat Manchester United, England’s most dominant side, in two Champions League Finals. Set up in a 4-3-3, Barcelona boasted few physically imposing players but featured arguably the most successful midfield trio in history and they prioritized possession and pressing over everything else. Xavi, Andres Iniesta, and Sergio Busquets outclassed United’s midfield in the two finals showing the world that the best players in the world might lack athletic physicality but could still dominate on the basis of passing, vision, and control. Pep’s reign at Barcelona popularized possession football world-wide and was the catalyst for a new generations of superstars whose game was based on technical ability and football IQ, rather than physical attributes. Pep also validated the concept of playing with a “false nine,” a striker who drops into the midfield to combine and allow wide midfielders to run into the empty space behind the defense. Pep chose to put Lionel Messi in this central role instead of using him out wide; the tactical move had devastating success.

The result of Pep’s success and style at Barcelona influenced the tactical makeup of the Premier League, as well as what types of players were most valued. Take for example, now retired central midfielder Paul Scholes, who played for Manchester United from 1993-2013. Scholes was always regarded as a top player for United and England but following Barcelona’s success his stock skyrocketed in Europe. Due to the increased emphasis on using holding midfielders to initiate attacks and midfield trios maintaining possession, Scholes moved away from the attacking midfield role and dropped deeper to showcase his world class passing ability (Cox, 2017, 250). This position change was only possible because of the role change of the holding midfielder from being defensively minded to a mix of defensive position and ball distribution. 2010 was the first time a player of Scholes’ size and technical ability was heralded as a world class player because the possession-based style suited his long range passing ability and intelligence. Yet, prior to this tactical shift, Scholes was regarded as less talented than his English midfielder counterparts Gerrard, Lampard, and Beckham (Cox, 2017, 350). After Pep’s success at Barcelona however, Scholes became regarded as one of the best Premier League midfielders of all time, primarily because of his success in a deeper role.

As teams continued to place greater emphasis on holding the ball longer and attacking in a more patient manner – partly in response to Barcelona’s dominance over English sides – a new generation of creative players entered the Premier League. Between 2010 and 2012, Santi Cazorla, David Silva, and Juan Mata were signed by Arsenal, Manchester City, and Chelsea, respectively. The Premier League has since grown accustomed to short, technical attacking midfielders who can play on the right, left or center in a 4-2-3-1 or 4-5-1, but these three signings signaled the emergence of that mold of player in England, a player who is on the pitch to simply create. The roles of Silva, Mata and Cazorla were developed around short passing, clever movement, and pinpoint through balls; it didn’t really matter where they were deployed, as they always played the same role (Cox, 2017, 362). All three players not only came from the Spanish division but were also a part of the successful Spanish national team at the 2010 World Cup and Euro 2012. This new breed of footballers in England weren’t traditional wingers or playmakers but assisters (Cox, 2017, 365). The immediate success of Silva, Mata and Cazorla popularized the concept of the assister and led to the arrivals of Mesut Ozil, Kevin De Bruyne and Christian Eriksen.

The final tactical evolution that reshaped the Premier League before Pep’s arrival in 2016 was the rise of pressing, something that Pep had also popularized at Barcelona. Tottenham Hotspur manager Mauricio Pochettino was the first manager to bring Pep’s pressing methods to England. As Cox notes, “Rather than sitting back and admiring the opposition’s pretty passing, teams increasingly pushed up and attempted to disrupt it” (Cox, 2017, 402). Teams in the Premier League now placed top priority on two tactics, keeping the ball and winning it back as quickly as possible to start devastating counter attacks. These two tactical concepts symbolized how much the tactical framework of the Premier League had been impacted by Pep prior to his arrival. Following 2010, the culture of Spanish football imprinted itself on English football in the shape of possession football and small versatile attacking midfielders responsible for assisting. Once a League where wingers were simply expected to work up and down the line and cross, wingers, as well as all positions, became all round players who could provide link up play, cut inside and shoot, cross and press effectively. As possession and pressing became the focus of Premier League tactics, it became obvious after Pep’s departure from his second coaching role at Bayern Munich that the Premier League would come calling. A self-proclaimed football purist who stays true to Total Football and Spanish philosophies, Pep could not turn down the challenge of toppling the League which he helped to shape from a far. While teams may aim to emulate aspects of Pep’s style, such as Liverpool in the 2012-2013 season and Arsenal for much of Wenger’s tenure, Pep’s ability to impose and execute a clear system and vision has stood out. Much of the English press questioned Pep’s ability to succeed upon his arrival at Manchester City in a League whose history was rooted in long ball, physical football regardless of the tactical evolution of the past decade. In his first year in England, Manchester City failed to win the Premier League or develop into a classic Pep team with the style of Barcelona or Bayern Munich. Yet, this season, Pep’s philosophy of possessing with a purpose and counter pressing has received all the plaudits as City has ripped the Premier League apart and won the title in convincing fashion.

Pep’s Tactical Framework

Pep’s appreciation for and utilization of the technical and creative aspects of players cannot be understated when discussing the success of Manchester City this past season. Pep establishes a culture of critical self-analysis, passing excellence and spatial understanding amongst his players. As famous striker Thierry Henry says about Pep: “He makes you understand how important it is to stay in your position, understand space, understand that the ball travels faster than anybody else, understand that you need to enjoy the game simply in order to win the game” (Bajkowski, 2018). Pep typically spends two hours per day discussing one-on-one the positional minutiae of what he demands from his players. It is not just the principles of position and movement that Pep develops, but the culture of technical and tactical intelligence that it perpetuates. “Pep doesn’t just give you orders,” said Gerard Pique. “He also explains why” (“Guardiola’s 16 Point Blueprint for Dominance,” 2016). Understanding Pep Guardiola as a person is essential to understanding how and why he implements the system he does. His coaching style integrates a holistic approach to player relationships and a combination of demanding results along with player development.

Although there are teams in the Premier League whose identity is based on possession and pressing and deploy 4-3-3, Manchester City’s tactical fluidity is unmatched in England. Pep experimented with a 3-1-4-2 formation for the first few matches of the 2017-2918 season but switched back to the 4-3-3 and stayed with it. The result was an unmatched season in Manchester City’s history: 59 wins, the most in a single season during the least two decades; 106 goals, four more than their previous 2013/14 season high of 102; and highest ever goal average at 2.8.

Before addressing the tactical make up of Pep’s City side, it is important to recognize the financial resources that Pep has at his disposal. Over the last two years that Pep has spent a staggering 448 million pounds. Basically, Pep can sign any player who fills a gap in his tactical model. For example, Benjamin Mendy, who signed for 57.50 million pounds, Danilo, who signed for 30 million pounds, Kyle Walker, who signed for 51 million pounds, and Ederson, who signed for 40 million pounds, were all contracted this summer to transform City’s defensive line into a dynamic back five, which also includes Vincent Kompany, who can dominate possession. Most clubs can’t sign any two players of this caliber in one window, but Pep has the resources to build his ideal group of players.

Pep’s System and Style of Coaching

Positionality of Possession with Purpose

At the heart of Pep’s tactical philosophy is the concept of possession, not simply as a means of defensive protection, but as the cornerstone of effective attacking play. The rise of possession has not resulted in a uniform practice of style. Moreover, it is common in the Premier League, as well as in other leagues, that teams aiming on winning the possession battle can change philosophy based on the opposition. But, with Manchester City and Pep, there is no such adaptation. Instead, Pep commits to possession with a purpose in every game and in every area of the pitch. “The secret is to overload one side of the pitch so the opponent must tilt its own defense to cope,” Pep says in Pep Confidential. “When you’ve done that, we attack and score from the other side. That’s why you have to pass the ball with a clear intention. Draw in the opponent, then hit them with the sucker punch” (“Guardiola’s 16 Point Blueprint for Dominance,” 2016). Although Pep has outstanding players at his disposal, the success of his possession model are nonetheless built on his strategies and tactics.

The foundation of Pep’s style at Manchester City is the positional interchange and freedom that exists between the front five attacking players and the overall shape of the team when in possession of the ball. A feature of City’s 4-3-3 shape that not only sets this City side apart from the rest of the Premier League but also differs from previous Pep teams, is the utilization of false full-backs to dominate possession. The traditional notion of what a full-back should do is mark the opposition’s wide attacker, distribute safely to nearby midfielders, and occasionally move forward and cross the ball from a wide area. Historically, full-backs slowly developed into potent attacking weapons, able to contribute to all aspects of play. At Manchester City, the full-backs are crucial for facilitating the creation of space for the two attacking midfielders, Silva and De Bruyne. Kyle Walker (right back) is extremely attack oriented and Fabian Delph (left back) is an inverted full-back who before this season spent his career playing central midfielder. Both are placed in more central positions to control the game from deep. As Constantin Eckner and Austin Reynolds write: “The additional protection at the back or in the zone ahead of the center-backs due to the addition of another player worked wonders” Eckner and Reynolds, 2018).

FIGURE 1: Manchester City Line-Up – 2017/2018 (Eckner and Reynolds, 2018)

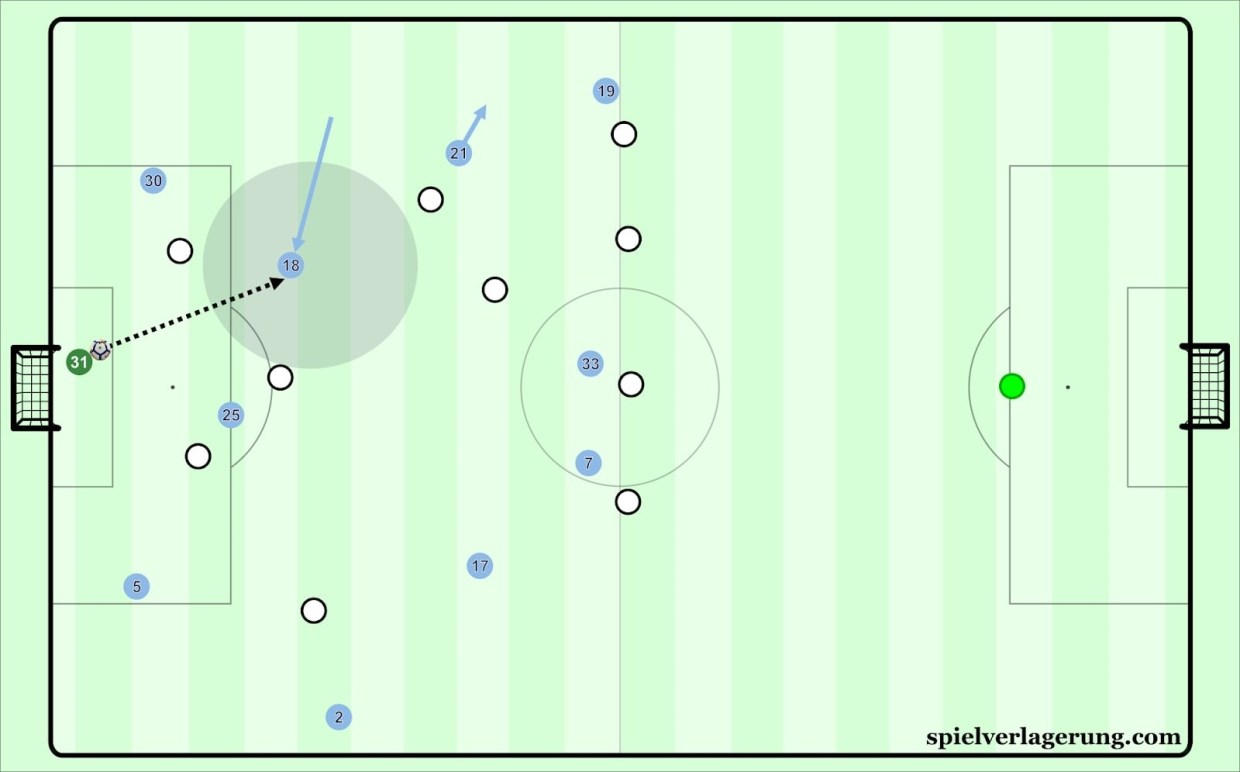

The roles that Delph and Walker fill are invaluable and unique, especially in relation to how the other full-backs in the Premier League are used. Walker consistently receives the ball in space due to his high and wide starting position and he is able to create 2 vs 1 situations in dangerous wide areas. Delph is essential for providing an extra man to the base of the midfield, but he is also able to provide defensive security for the left sided attacking midfielder in pressing situations (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2: Delph and the False Full Back (https://spielverlagerung.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2-18/01/2018-01-02_ManCity_Delph-FalseFB.png)

The involvement of Delph comes early in the process of generating offensive opportunities. Averaging 73.4 passes per match, Delph is able to connect with his midfielders consistently because of Pep’s system and how it allows Delph to utilize his midfield-oriented technical abilities. It seems a trivial possession tactic but it is crucial to understanding the offensive success of Manchester City, and it is crucial to understanding how the origin of each possession results in a shot on frame or even finding the back of the net. Outside backs of other top table teams are not seeing numbers such as 37.8 passes per match for Danny Rose, 40.8 ppm for Marcos Alonso, 42.8 ppm for Ashley Young, and Nacho Monreal for 61.4 ppm.

Kyle Walker, with 73.8 ppm, occupies the complementary role of a more offensive wing back. It is important to distinguish the two passing statistics between Walker and Delph, as they both possess relatively close, and high, passing averages compared to other top flight wing backs. The involvement of Walker in offense-oriented play is vital to Manchester City’s objective to pull apart the defensive structure of their opponents. With his pace and athleticism, Walker has been able to provide six assists this season, which is only matched by Tottenham Hotspur’s Ben Davies, who is especially deft at crossing the ball into dangerous spaces rather than engaging in a deliberate build up.

The passing ability and spatial understanding of City’s back line facilitate their ability to maintain possession in all areas of the pitch. While John Stones, Laporte, Kompany and Otimenti are more than competent in possession, the signing of goalkeeper Ederson this past summer has revolutionized City’s capacity for passing around the opposition’s press. When City face teams that high press them as a tactic to dismantle their possession, the Brazilian keeper plays a highly influential role in helping City maintain their possession advantage: “The goalkeeper offers an extra man and allows for circulation to take place in deeper areas. When teams go and pressure the goalkeeper or centre-backs that are in line with the keeper, spaces will open up high up the pitch” (Ewckner and Reynolds, 2018). Ederson is proficient with short and medium length distribution but he has grown to be world class in his long range distribution which allows him to single handedly start attacking waves. His ability to drive passes from dead balls and side volleys into the attacking third with Xavi-like accuracy is unprecedented for a goalkeeper. Ederson is capable of dismantling pressing schemes by either playing over them or around them.

Ederson has completed 69.5%, of his attempted 965 passes in the Premier League, compared to 69% completed by Simon Mignolet of Liverpool, the next most accurate goalkeeper (Spencer, 2017). Not only has Ederson been an outstanding shot stopper for Manchester City, but he has also played an unusual role as a deeper line alternative when possessing the ball between the back line. Only Courtois, the keeper for Chelsea, has completed more than 60% of his passes. Another notable difference between Ederson and other comparable goalkeepers is that “Ederson has played as much as 71% of his Premier League passes short this season […]. Courtois has played just under half (49%) of his passes short, while Lossl has played fewer than one in three of his passes short, with 71% going long” (Spencer, 2017). It is common practice for teams to drop a central defensive midfielder in between the center backs in order to provide support, but there are many advantages to having a goalkeeper with the ability and composure to play the role of any other distributor from the back end, allowing more players to move and exploit unoccupied space in the midfield.

The stars of Pep’s side this year have undoubtedly been the attacking midfield duo of David Silva and Kevin De Bruyne. Kevin De Bruyne with eight goals and 16 assists, and David Silva with nine goals and 11 assists, together combining in the midfield for 27 assists, account for most of the goals generated for any given forward or striker they are working with, whether it be Aguero, Sane, Sterling, or Gabriel Jesus. Both Silva and De Bruyne float into wide areas for combination plays with wingers from time to time or swap with wingers to create gaps in the opponent’s defense. They aim to play in between the lines of the opposition’s defense and midfield lurking for the ball to quickly play a splitting through ball. The difference between these two creators and the pair Pep established at Barcelona, Xavi and Iniesta, is that the Barcelona pair stayed much more central. Silva and De Bruyne, however, are given more freedom to drift into wide spaces, highlighting Pep’s trust in them to control the game from all sectors of the pitch. A main reason for the success of Silva and De Bruyne is the “usage of blindside movements in order to free up space for themselves” (Eckner and Reynolds, 2016). David Silva utilizes this form of movement to find tight channels in wider areas in order to combine mainly with left winger Leroy Sane. This allows Silva to play to his strengths, displaying his silky footwork and craftiness in tight areas to outwit the opposition. Conversely, De Bruyne will drift into more central half-spaces showing patience in his movement as a way to create space for himself (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: The Role of DeBruyne (https://spielverlagerung.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2-18/01/2018-01-02_ManCity_DeBruyne-Goal.png)

Much credit this season is also due to the young and exuberant wingers Raheem Sterling and Leroy Sane. By the end of the season, Sterling, had collected 18 goals and 11 assists, and Sane, 10 goals and 15 assists. The interchange allows these two players to not only focus on getting in behind or making traditional combination plays, but it encourages the front five to become creative when working with each other and it allows for success when exchanging space between one another. What cannot be ignored is the rate at which Sane and Sterling have produced goals, whether it be scoring or delivering the optimal final pass for the resulting goal scorer. The focus becomes more centered on the new game situations that Sane and Sterling have found themselves dealing with given Pep’s system and how efficient they have been in the process of adapting to their respective positions.

Normally the two wingers remain as close to the touchline as possible, to stretch the opposition’s back line and create pockets of space for Silva and De Bruyne to find. That being said, both Sane and Sterling are also able to play in more central, tighter areas as well. The rise of these two players speaks volumes to Pep’s coaching acumen, transforming each player into a proficient goal scorer and creator in seemingly no time. In response to questions about Pep’s influence on his game, Sterling comments: “When I used to dribble, I’d be on the wing and I’d control it with the outside of my foot – it slows the ball down. He brings you back to what you used to do with the under-eights, open your body up, gets the rhythm going again – little details like that” (Eckner and Reynolds, 2018).

The difference in Sterling’s play is quantifiable over the past couple of seasons at Manchester City. In 31 appearances during the 2015/16 season, Sterling had six goals and two assists. His passing rate per match was 27.29, with crosses totaling 68. In the 2016/17 season, Sterling increased his passes per match to 31.30, and his crossing total remained at 84. In this recent season, Sterling had seven goals and six assists. More familiar with Pep’s system, Sterling finds himself with 35.45 passes per match and only 39 crosses. Now in a more central role, Sterling is more likely to pass or keep the ball than to cross the ball and risk losing possession or facing a counter-attack.

The more traditional roles within City’s system fall on Fernandinho and Sergio Aguero and Gabriel Jesus, the holding midfielder and the two strikers, who rotate for the lone forward spot. Although these players fill roles that are typical in other top sides around the world, their functions serve a pivotal purpose in Pep’s formation due to the movement around them. Fernandinho’s purpose is evident in each game he plays: “Instead of moving up and down field, the no. 6 is specifically responsible for covering the two or three players in front of him, while also providing additional protection at the back, especially when one of the centre-backs advances in build-up is pulled away due to strict man-marking.(source).” The Brazilian number six for Pep’s side provides stability on both sides of the ball and stays in the central pocket between the center backs and attacking midfielders. This season Fernandinho has completed more passes than any other City player and is only behind David Silva in touches. Fernandindinho’s distribution is vital in establishing and maintaining the team’s tempo and he serves as the pivot in City’s central control of possession. Dropping deep between the two center backs when they drift out wide, especially when Ederson has the ball, has become a norm for City’s number six. He is able to bring the opposition’s attacking midfielders out of position to follow him, creating more space for Silva and De Bruyne to drift into. Against Everton on March 31, 2018, Fernandinho ended the match with almost as much possession as Everton had throughout the entire match: 14.5 % for Fernandinho compared to 17.9% for Everton. Many holding midfielders in the Premier League, including Granit Xhaka (Arsenal), N’golo Kante (Chelsea), or Nemanja Matic (Manchester United), are expected to distribute the ball swiftly and simply and screen the back four defensive positions, but Fernandinho’s ability, especially when in possession of the ball, clearly stands out. While many argue that N’golo Kante is the best central midfielder in the Premier League, Fernandinho is in many ways the lynchpin of Manchester City’s title winning side; he produces 87.5 passes per match on average, at a 90.1% success rate compared to the likes of former PFA player of the year N’golo Kante who has 46.7 passes per match, at an 90.4% success rate. The only player who seems to be finding higher success in pass rate is Mousa Dembele with 91.7 passes but that is only supported by 50.79 passes per game. It must also be noted that the Brazilian is connecting productively with players who are putting themselves in threatening positions during build-up, as demonstrated by Manchester City’s Premier League leading 2.79 goals scored per match; Liverpool comes in second with 2.3 and Tottenham in third with 2.0 goals per match.

In regards to the strikers Gabriel Jesus and Sergio Aguero, when either are fielded as a striker, their purpose is similar to other teams who aim to possess and brake at speed. Both are required to combine with the other attacking players and circulate possession while making runs in behind the defense to stretch the opposition out. Jesus and Aguero are two of the most potent finishers the League has seen, usually finding themselves in the right position to finish off a lengthy City build-up. The two strikers are perfectly suited to City’s system and style due to their technical proficiency in passing and dribbling in tight areas and both are unselfish footballers. Furthermore, in Pep’s eyes, possession is nothing if it does not lead to goals; thus, it is essential to have strikers who are clinical in the box. Sergio Aguero and Gabriel Jesus have tallied up goals in numbers and quality throughout the season. Aguero, finding helpers from 11 different Manchester City names for his team leading 21 goals, and Jesus, from nine different players accounting for his 13 goals, the two strikers work with all of Pep’s strategies and expectations, each adjusting in such a way that they can still accrue significant points for the team. Understanding that goal scoring comes not only from the strikers, and that the scoring is well distributed amongst all of the attacking five players, evacuate their familiar zones on the field in order to create spaces for their teammates and find goal scoring opportunities, rather than having their teammates have to find the space on their own, or force the ball into a unpredictable situation where possession may be lost.

Aspects of Distribution

Pep has established great success implementing the focus of playing out of the back, hitting diagonal balls and low crosses. In order to disrupt the opposition’s defensive structure, City must be able to move the ball around the back with speed to draw the opposition out of position in order to create half spaces for attacking players. Because of the passing strength of center backs Vincent Kompany, Laporte, Otamendi and John Stones, City are able to get the ball into the middle third consistently. Nicolas Otamendi had the most passes on the team with 3.074 passes, 90.41 passes per game. The full-backs are closer to the defenders during build-up, allowing for more stable circulation. Rather than forcing passes up the field into congested areas where the wing-backs previously were, the deeper position of the full-backs forces opponents to move up their lines in order to close them down. The result of this tactical shape results in more space for the midfield trio to move into, emphasizing the importance that width has in City’s system (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4: The Role of Otamendi (https://spielverlagerung.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2-18/01/2018-01-02_ManCity_Otomendi-SteppingUp.png)

Another way possession is established and maintained is through the utilization of diagonal passing. The tactical reason for diagonal distribution is that “diagonal passes elicit more of a response from the opponents when it comes to shifting, as they must change their reference point both horizontally and vertically. Square or straight passes do not require such shifting for the opposite reason” (Eckner and Reynolds, 2018). Diagonal passing is crucial to City’s style of play. The majority of teams in the Premier League hold a preference for covering positional passing options instead of applying direct pressure to a defender carrying the ball forward. Aerial diagonal balls to the wingers are especially effective for City. “When these passes are played, Sane and Sterling are isolated due to the opponents being overly fixated on the close passing options.” Therefore, “Sane and Sterling frequently have a lot of space for dribbling by the player defending, and City move into chance creation mode” (Eckner and Reynolds, 2018) (see Figure 5). The application of diagonal switches is an efficient method of bypassing the opponent’s defense while exploiting the individual skill of City’s players.

FIGURE 5: Sane and the Diagonal Pass (https://spielverlagerung.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2-18/01/2018-01-02_ManCity_Sane-DiagonalPass.png)

Pressing and Transitioning

Pressing systems in the Premier League have been on the rise since Pep successfully instituted pressing methods at Barcelona at the turn of the decade. Of course, all teams employ different pressing schemes based on their own personnel and the opposition, but a successful press demands intense physical and mental focus, coupled with a deep understanding of space and constant communication through visual cues. Pep’s pressing plan at City has three phases, but what sets Pep apart from other managers is his implementation of counter-pressing and attacking rest-defensive positions. The first phase of the press comes from City’s front line who pressure the defenders who are in possession. Once City’s highest players are bypassed, Silva and De Bruyne move forward to compress the half space between the opposition’s defense and midfield, igniting the second phase of the press. If the opposition navigates through the first two phases then City’s shape will shift into a 4-1-5. “Deeper into the season, City started using curve-runs up front more frequently in order to set up pressing trap. If they are not able to successfully force the early turnover, City typically transition into a 4-1-5, with the two wingers dropping back on the outside lanes to potentially have double coverage there. The third phase of pressing sees them in a 4-5-1, as the two centre-midfielders move back and join Fernandinho to close down the middle” (Eckner and Reynolds, 2018).

The separation in successful pressing between champions Manchester City and other pressing sides like Liverpool or Spurs lies in the theory of counter pressing. “The times in which City have either just lost or recovered possession define their style of play as much as their moments in possession” (Eckner and Reynolds, 2018). Famous for his “Six Second Rule” at Barcelona, signaling the time it should take for Barcelona to regain possession after losing the ball, Pep has instilled a very similar counter pressing model at City which aims to block passing lanes for the player in possession as quickly as possible. Pep’s side is ironically most dangerous after they have lost the ball. The times they carelessly lose possession are few and far between; therefore, when they do, opposing teams immediately aim to counter attack with pace. Yet, that is when City seem to strike with alarming accuracy because their opponents are more spread out in order to facilitate a quick counter attack. It is difficult to counter attack against Manchester City through the center of the pitch. Their ability to counter press is heavily dependent on the starting positions of players once they have lost possession, which is referred to as rest defense. Once the opposition intercepts Silva’s pass, City are ready to defend counter-attacks in the center due to the 5 vs 2 advantage in their rest-defense, while also being able to pick up any runners from the opponents (see Figure 6). Pep values outnumbering the opponent in the center at all

FIGURE 6: The Rest Defense (https://spielverlagerung.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2-18/01/2018-01-02_ManCity_Res-Defense.png)

times, thus hampering the opposition’s ability to play to feet centrally. Consequently, the best option becomes to play a through ball, but, due to the back four’s high line and Ederson’s ability to step out quickly, the chances of succeeding in this approach are slim. Pep organizes his team in possession so that when possession is lost, they are adequately balanced to deal with transitions that happen to break through the initial counter-press. For instance, if City are attacking down the left side of the pitch, Walker will help cover for the center-backs and Fernandinho will reside in front of the first line of defense preventing anything down the middle, with a distance occupied that can have him move into a covering spot if needed. City’s ideal counter press can be seen in Figure 7: Because the inverted full-back provides more protection in the number six space and the two advanced midfielders can drift laterally more freely, City create plenty of pressure around the ball carrier who intends to trigger the transition attack.

FIGURE 7: Counterpressing (https://spielverlagerung.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2-18/01/2018-01-02_ManCity_Counterpressing.png)

In terms of attacking transitions, “Rather than aiming to counter whenever possible, City wisely pick their moments to unleash their weapons when their opponents are spread out during their attack” (Eckner and Reynolds, 2018). Due to the importance of width when attacking, many Premier League sides are stretched when City win the ball back. This results in empty space for the trio of Sane, Aguero and Sterling to burst onto a through ball from Silva or De Bruyne, who had nine and 14 assists respectively. After the through ball has been played, it usually culminates in a low cross from Sterling or Sane to either Aguero, Jesus or a midfielder running to the top of the box. Sane had 11 assists while Sterling had seven; fantastic returns for the wide creators.

CONCLUSION

Through examining the positionality, distribution, and transitioning and pressing of Pep’s system at Manchester City, it is clear why they excelled during the past season. Pep provides his players with a clear tactical and philosophical blueprint and engages with them in a manner different from the other top managers in the Premier League. Manchester City had a historic 2017-2018 Premier League season; not only did Guardiola win the title, but his City side went on an 18 game winning streak in the process. Beyond his strategic and tactical innovations, Pep is also able to personally connect with his players in order to get the best out of them. It seems as though Pep has recruited the perfect blend of experience and youth, technique and physicality, all determined players, to lead Manchester City. During the 2017-2018 season, Pep implemented a tactical system that focused on the quality of his players and their ability to keep the ball and create chances. It will be very interesting to see how other clubs react to what Manchester City achieved this past season in terms of tactics and financial investment. One thing is for sure though: the Guardiola style and system has been successful everywhere he has gone. After years of shaping the tactics of the Premier League from afar, Pep has finally conquered it from within.

REFERENCES

1. Bajkowski, S. (2018) Man City Manager Pep Guardiola’s Extreme Methods to Improve Players. Manchester Evening News. Retrieved at: https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/sport/football/football-news/man-city-guardiola-training-henry-14364098.

2. Cox, M. (2017) The Mixer. London: HarperCollins.

3. Eckner, C., & Reynolds, A. (2018) How Pep’s Citizens have Taken Over England.” Spielverlagerung. Retrieved at: https://spielverlagerung.com/2018/01/02/how-peps-citizens-have-taken-over-england/.

4. Guardiola’s 16 Point Blueprint for Dominance. His Methods Management and Tactics. FourFourTwo. Retrieved at: https://www.fourfourtwo.com/us/features/long-read-guardiolas-16-point-blueprint-dominance-his-methods-management-and-tactics#bhTEB8J7386PYbOc.99.

5. Spencer, J. (2017) Stats Reveal just how Suited New #1 Ederson is Pep Guardiola’s Man City System. 90Min. Retrieved at: https://www.90min.com/posts/5833855-stats-reveal-just-how-suited-new-1-ederson-is-to-pep-guardiola-s-man-city-system.