Abstract

In spring 1999, almost a decade ago, the first author published in The Sport Journal an article titled “Music in Sport and Exercise: Theory and Practice.” The present article’s origins are in that earlier work and the first author’s research while a master’s student at the United States Sports Academy in 1991–92. To a greater degree than in the original 1999 article, this article focuses on the applied aspects of music in sport and exercise. Moreover, it highlights some new research trends emanating not only from our own publications, but also from the work of other prominent researchers in the field. The content is oriented primarily towards the needs of athletes and coaches.

Music in Sport and Exercise: An Update on Research and Application

With the banning of music by the organizers of the 2007 New York Marathon making global headlines, the potentially powerful effects of music on the human psyche were brought into sharp focus. In fact, music was banned from the New York Marathon as part of the wider USA Track & Field ban on tactical communications between runners and their coaches. The marathon committee upheld this ban, which is often otherwise overlooked, justifying its action in terms of safety.

The response to the ban was emphatic. Hundreds of runners flouted the new regulation and risked disqualification from the event—such was their desire to run to the beat. Experience at other races around the world confirms the precedent set in New York; try to separate athletes from their music at your peril! But why is music so pivotal to runners and to sports people from a wide variety of disciplines?

How Music Wields an Effect

In the hotbed of competition, where athletes are often very closely matched in ability, music has the potential to elicit a small but significant effect on performance (Karageorghis & Terry, 1997). Music also provides an ideal accompaniment for training. Scientific inquiry has revealed five key ways in which music can influence preparation and competitive performances: dissociation, arousal regulation, synchronization, acquisition of motor skills, and attainment of flow.

Dissociation

During submaximal exercise, music can narrow attention, in turn diverting the mind from sensations of fatigue. This diversionary technique, known to psychologists as dissociation, lowers perceptions of effort. Effective dissociation can promote a positive mood state, turning the attention away from thoughts of physiological sensations of fatigue. More specifically, positive aspects of mood such as vigor and happiness become heightened, while negative aspects such as tension, depression, and anger are assuaged (Bishop, Karageorghis, & Loizou, 2007). This effect holds for low and moderate exercise intensities only; at high intensities, perceptions of fatigue override the impact of music, because attentional processes are dominated by physiological feedback, for example respiration rate and blood lactate accumulation.

Research shows that the dissociation effect results in a 10% reduction in perceived exertion during treadmill running at moderate intensity (Karageorghis & Terry, 1999; Nethery, 2002; Szmedra & Bacharach, 1998). Although music does not reduce the perception of effort during high intensity work, it does improve the experience thereof: It makes hard training seem more like fun, by shaping how the mind interprets symptoms of fatigue. While running on a treadmill at 85% of aerobic capacity (VO2max), listening to music will not make the task seem easier in terms of information that the muscles and vital organs send the brain. Nevertheless, the runner is likely to find the experience more pleasurable. The bottom line is that during a hard session, music has limited power to influence what the athlete feels, but it does have considerable leverage on how the athlete feels.

Arousal Regulation

Music alters emotional and physiological arousal and can therefore be used prior to competition or training as a stimulant, or as a sedative to calm “up” or anxious feelings (Bishop et al., 2007). Music thus provides arousal regulation fostering an optimal mindset. Most athletes use loud, upbeat music to “psych up,” but softer selections can help to “psych down,” as well. An example of the latter is two-time Olympic gold medalist Dame Kelly Holmes’s use of soulful ballads by Alicia Keys (e.g., “Fallin’” and “Killing Me Softly”) in her pre-event routine at the Athens Games of 2004. While the physiological processes tend to react sympathetically to music’s rhythmical components, it is often lyrics or extramusical associations that make an impact on the emotions. Ostensibly, fast tempi are associated with higher arousal levels than slow tempi.

Karageorghis and Lee (2001) examined the interactive effects of music and imagery on an isometric muscular endurance task which required participants to hold dumbbells in a cruciform position for as long as possible. Males held 15% of their body weight and females held 5% of their body weight. The authors found that the combination of music and imagery, when compared to imagery only, music only, or a control condition, enhanced muscular endurance (see Figure 1), although it did not appear to enhance the potency of the imagery. The main implication of the study was that employing imagery to a backdrop of music may be a useful performance-enhancement strategy that can be integrated in a pre-event routine.

Figure 1. Bar chart illustrating mean scores (+ 1 SD) for isometric muscular endurance under conditions of imagery only (A), motivational music (B), motivational music and imagery (C), and a no music/imagery control (D).

Synchronization

Research has consistently shown that the synchronization of music with repetitive exercise is associated with increased levels of work output. This applies to such activities as rowing, cycling, cross-country skiing, and running. Musical tempo can regulate movement and thus prolong performance. Synchronizing movements with music also enables athletes to perform more efficiently, again resulting in greater endurance. In one recent study, participants who cycled in time to music found that they required 7% less oxygen to do the same work as compared to cycling with background (asynchronous) music (Bacon, Myers, & Karageorghis, 2008). The implication is that music provides temporal cues that have the potential to make athletes’ energy use more efficient.

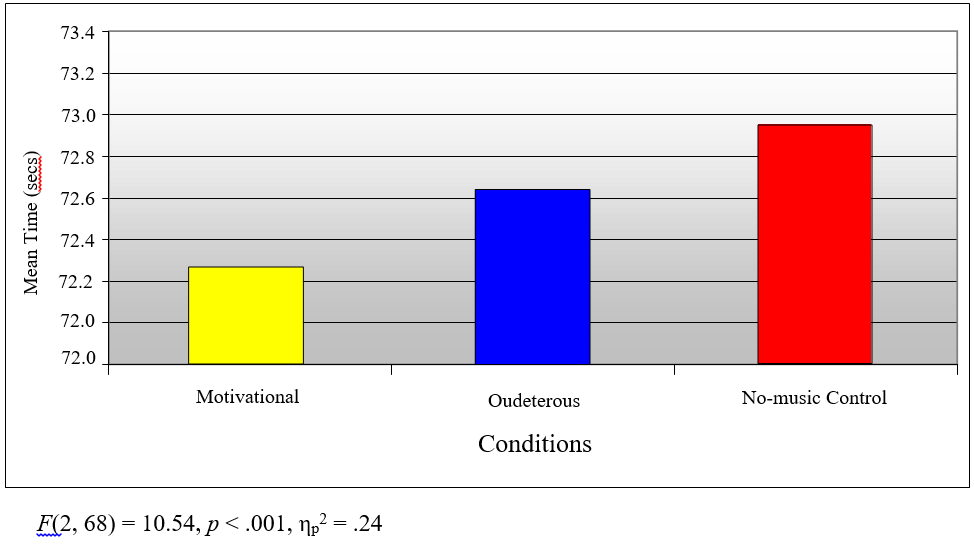

The celebrated Ethiopian distance runner Haile Gebrselassie is famous for setting world records running in time to the rhythmical pop song “Scatman.” He selected this song because the tempo perfectly matched his target stride rate, a very important consideration for a distance runner whose aim is to establish a steady, efficient cadence. The synchronization effect in running was demonstrated in an experimental setting by Simpson and Karageorghis (2006), who found that motivational synchronous music improved running speed by ~.5 s in a 400-m sprint, compared to a no-music control condition (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mean 400 m times for synchronous motivational music, synchronous oudeterous music, and a no-music control.

Acquisition of Motor Skills

Music can impact positively on the acquisition of motor skills. Think back to elementary school days and your initial physical education lessons, which were probably set to music. Music-accompanied dance and play created opportunities to explore different planes of motion and improve coordination. Scientific studies have shown that the application of purposefully selected music can have a positive effect on stylistic movement in sport (Chen, 1985; Spilthoorn, 1986), although there has been no recent research to build upon initial findings.

There are three plausible explanations for the enhancement of skill acquisition through music. First, music replicates forms of bodily rhythm and many aspects of human locomotion. Hence, music can transport the body through effective movement patterns, the body providing an apparent visual analogue of the sound. Second, the lyrics from well-chosen music can reinforce essential aspects of a sporting technique. For instance, in track and field, the track “Push It” (by Salt-n-Pepa) is ideal for reinforcing the idea that the shot should be put, not thrown; throwing the shot is the most common technical error. Third, music makes the learning environment more fun, increasing players’ intrinsic motivation to master key skills.

Attainment of Flow

The logical implication of study findings concerning music’s effects on motivational states is that music may help in the attainment of flow, the zenith of intrinsic motivation. Recent research in sports settings has indeed found that music promotes flow states. Using a single-subject, multiple-baselines design, Pates, Karageorghis, Fryer, and Maynard (2003) examined the effects of pre-task music on flow states and netball shooting performance of three collegiate players. Two participants reported an increase in their perception of flow, and all three showed considerable improvement in shooting performance. The researchers concluded that interventions including self-selected music and imagery could enhance athletic performance by triggering emotions and cognitions associated with flow. Karageorghis and Deeth (2002), furthermore, investigated the effects of motivational music on flow during a multistage fitness test. The multiple dimensions of the flow experience were represented by the factors incorporated in the Flow State Scale (FSS) developed by Jackson and Marsh (1996). When compared to oudeterous music and a no-music control condition, motivational music led to increases in several FSS factors.

Selecting Music for Sport and Exercise

Type of Activity

An athlete searching for music to incorporate in training and competition should start by considering the context in which he or she will operate (Karageorghis, Priest, Terry, Chatzisarantis, & Lane, 2006). What type of activity is being undertaken? How does that activity affect other athletes or exercisers? What is the desired outcome of the session? What music-playing facilities are available? Some activities lend themselves particularly well to musical accompaniment, for example those that are repetitive in nature: warm-ups, weight training, circuit training, stretching, and the like. In each case, the athlete should make selections (from a list of preferred tracks) that have a rhythm and tempo that match the type of activity to be undertaken. To assess the motivational qualities of particular music, the Brunel Music Rating Inventory (BMRI) may be used (Karageorghis, Terry, & Lane, 1999), as may its derivative, the BMRI-2 (Karageorghis et al., 2006).

One of the latest developments in the music-in-sport field is London’s Run to the Beat half-marathon, an event that will feature scientifically selected motivational music performed live by musicians positioned along the route (Run to the Beat: London’s Half-Marathon, n.d.). Our research team has been instrumental in managing the music policy for Run to the Beat and in ensuring that runners are delivered music that is appropriate to their preferences and sociocultural backgrounds. We have gathered relevant information from the half-marathon’s website and used it in prescribing musical selections contoured to the event’s motivational and physiological demands.

Intensity of Activity

An athlete or exerciser whose goal during warm-up is elevating the heart rate to 120 beats per minute should select accompanying music that has a tempo in the range of 80–130 beats per minute. Successive tracks should create a gradual rise in music tempo to match the intended gradual increase in heart rate. Moreover, segments of music can be tailored to various components of training, so that, for example, work time and recovery time are punctuated by music that is alternately fast and loud or slow and soft. This approach is especially well suited to highly structured sessions such as circuit or interval training. The authors have used this technique with collegiate athletes engaged in a tough weekly circuit training session, and the upshot has been a 20% improvement in attendance.

Our recent research has uncovered the tendency among athletes and exercisers to coordinate bursts of effort with those specific segments of a musical track they find to be especially motivating. We refer to the phenomenon as segmentation (Priest & Karageorghis, 2008). The segmentation effect is particularly strong if the individual knows the musical track very well and can anticipate the flow of the music. It is also beneficial to match the tempo of music with the intensity of the workout. For example, when cycling at around 70% of one’s aerobic capacity, mid-tempo music (115–125 beats per minute) is more effective than faster music (135–145 beats per minute) (Karageorghis, Jones, & Low, 2006; Karageorghis, Jones, & Stuart, 2008).

Delivery of Music

Coaches and athletes must choose how selected tracks will be delivered before or during training or competition. If others are training nearby and might be disturbed by one’s music, it should be delivered via an MP3 player. Music intended to enhance group cohesion or inspire a group of athletes is best delivered with a portable hi-fi system or stadium public address system. If distraction is an important consideration, the volume at which music is played should be set quite high, but not high enough to cause discomfort or leave a ringing in the ears. Indeed, sound at a volume above 75 dB delivered during exercise—when blood pressure in the ear canal is elevated—can cause minor temporary hearing loss (Alessio & Hutchinson, 1991).

Selection Procedure

The researchers suggest accompanying training activities with music, to enable athletes to tap into the power of sound. To start, assemble a wide selection of familiar tracks that meet the following six criteria: (a) strong, energizing rhythm; (b) positive lyrics having associations with movement (e.g., “Body Groove” by the Architects Ft. Nana); (c) rhythmic pattern well matched to movement patterns of the athletic activity; (d) uplifting melodies and harmonies (combinations of notes); (e) associations with sport, exercise, triumph, or overcoming adversity; and (f) a musical style or idiom suited to an athlete’s taste and cultural upbringing. Choose tracks with different tempi, to coincide with alternate low-, medium-, and high-intensity training.

A further consideration is variety among selections. A study we published of data from a major fitness chain in the United Kingdom (Priest, Karageorghis, & Sharp, 2004) indicated that variety in the selections was paramount. Table 1 presents titles of motivational tracks suitable for different components of a single training session with a specific individual in mind.

Table 1

Example Motivational Music for Training-Session Components of Different Exercise Intensities

Workout Component

Title

Artist(s)

Tempo, in Beats per Minute

Mental preparation

“Umbrella”

Rihanna Ft. Jay Zee

89

Warm-up activity

“Gettin’ Jiggy With It”

Will Smith

108

Stretching

“Lifted”

The Lighthouse Family

98

Strength component

“Funky Cold Medina”

Tone Loc

118

Endurance component

“Rockafeller Skank

(Funk

Soul Brother)”

Fatboy Slim

153

Warm-down activity

“Whatta Man”

Salt-n-Pepa

88

Conclusion

We have established that there are many ways in which music can be applied to both training and competition. The effects of carefully selected music are both quantifiable and meaningful. As Paula Radcliffe, the world record–holding marathoner, has said, “I put together a playlist and listen to it during the run-in. It helps psych me up and reminds me of times in the build-up when I’ve worked really hard, or felt good. With the right music, I do a much harder workout.”

The findings we have discussed lead to the possibility that the use of music during athletic performance may yield long-term benefits such as exercise adherence and heightened sports performance, through a superior quantity and quality of training. Although many athletes today already use music, they often approach its use in quite a haphazard manner. We hope that through applying the principles outlined in this article, athletes and coaches will be able to harness the stimulative, sedative, and work-enhancing effects of music with greater precision.

References

Alessio, H. M., & Hutchinson, K. M. (1991). Effects of submaximal exercise and noise exposure on hearing loss. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 62, 414–419.

Bacon, C., Myers, T., & Karageorghis, C. I. (2008). Effect of movement-music synchrony and tempo on exercise oxygen consumption. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Bishop, D. T., Karageorghis, C. I., & Loizou, G. (2007). A grounded theory of young tennis players’ use of music to manipulate emotional state. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 29, 584–607.

Chen, P. (1985). Music as a stimulus in teaching motor skills. New Zealand Journal of Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 18, 19–20.

Jackson, S. A., & Marsh, H. W. (1996). Development and validation of a scale to measure optimal experience: The Flow State Scale. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 18, 17–35.

Karageorghis, C. I. (1999). Music in sport and exercise: Theory and practice. The Sport Journal, 2(2). Retrieved March 28, 2007, from http://www.thesportjournal.org/1999Journal/Vol2-No2/Music.asp

Karageorghis, C. I., & Deeth, I. P. (2002). Effects of motivational and oudeterous asynchronous music on perceptions of flow [Abstract]. Journal of Sports Sciences, 20, 66–67.

Karageorghis, C. I., Jones, L., & Low, D. C. (2006). Relationship between exercise heart rate and music tempo preference. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 26, 240–250.

Karageorghis, C. I., Jones, L., & Stuart, D. P. (2008). Psychological effects of music tempi. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 29, 613-619.

Karageorghis, C. I., & Lee, J. (2001). Effects of asynchronous music and imagery on an isometric endurance task. In International Society of Sport Psychology, Proceedings of the World Congress of Sport Psychology: Vol. 4 (pp. 37–39). Skiathos, Greece.

Karageorghis, C. I., Priest, D. L., Terry, P. C., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., & Lane, A. M. (2006). Redesign and initial validation of an instrument to assess the motivational qualities of music in exercise: The Brunel Music Rating Inventory–2. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24, 899–909.

Karageorghis, C. I., & Terry, P. C. (1999). Affective and psychophysical responses to asynchronous music during submaximal treadmill running. Proceedings of the 1999 European College of Sport Science Congress, Italy, 218.

Karageorghis, C. I., & Terry, P. C. (1997). The psychophysical effects of music in sport and exercise: A review. Journal of Sport Behavior, 20, 54–68.

Karageorghis, C. I., Terry, P. C., & Lane, A. M. (1999). Development and initial validation of an instrument to assess the motivational qualities of music in exercise and sport: The Brunel Music Rating Inventory. Journal of Sports Sciences, 17, 713–724.

Nethery, V. M. (2002). Competition between internal and external sources of information during exercise: Influence on RPE and the impact of the exercise load. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 42, 172–178.

Pates, J., Karageorghis, C. I., Fryer, R., & Maynard, I. (2003). Effects of asynchronous music on flow states and shooting performance among netball players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4, 413–427.

Priest, D. L., Karageorghis, C. I., & Sharp, N. C. C. (2004). The characteristics and effects of motivational music in exercise settings: The possible influence of gender, age, frequency of attendance, and time of attendance. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 44, 77–86.

Priest, D. L., & Karageorghis, C. I. (2008). A qualitative investigation into the characteristics and effects of music accompanying exercise. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Run to the Beat: London’s Half-Marathon (n.d.). Music: The Science behind Run to the Beat. Retrieved July 3, 2008, from http://www.runtothebeat.co.uk/music.html

Simpson, S. D., & Karageorghis, C. I. (2006). The effects of synchronous music on 400-m sprint performance. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24, 1095–1102.

Spilthoorn, D. (1986). The effect of music on motor learning. Bulletin de la Federation Internationale de l’Education Physique, 56, 21–29.

Szmedra, L., & Bacharach, D. W. (1998). Effect of music on perceived exertion, plasma lactate, norepinephrine and cardiovascular hemodynamics during treadmill running. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 19, 32–37.